Cullman County businessman, musician Nate Harvell dies at age 84

Published 3:23 am Wednesday, March 5, 2025

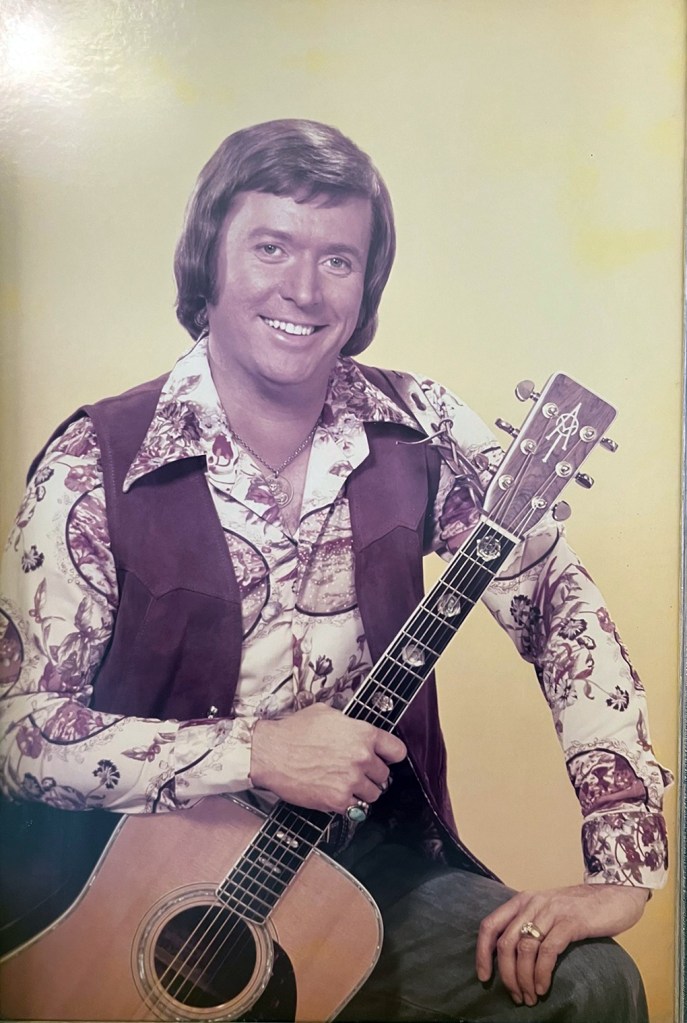

- Bennie Nathan "Nate" Harvell. Courtesy photo

On August 17, 1940, Bennie Nathan “Nate” Harvell was born in a country Cullman house on the eastern outskirts of the city limits. He was one of four brothers and one sister raised in Cullman County by Ben and Ruby Harvell. They faced hardships of poverty brought on by harsh circumstances tough for most people living in the same community today to imagine.

As a small child, Nate began routinely dragging pots and pans from a lower kitchen cupboard and, like innumerable children in place and time before and after, banging and clanging to his young heart’s desire. Only around the age of four, his father began to note that Nate’s pot-pan drum sessions were beginning to incorporate a sense of form and rhythm that sounded more like music than childish playing.

Sensing that the youngster had a natural inclination to music, Nate’s father purchased a second-hand fiddle. After spending a little time with the instrument and the odd drop-in visitor showing him a thing or two they knew musically, the young Nate began playing and eventually showcasing the same natural musical talent his father had heard in the pots and pans.

Trending

As he grew older, Nate was able to get his hands on a guitar and further improved in his playing. In addition to cultivating a knack for the fretted instrument, the budding musician enjoyed coming up with words for songs like those he’d heard on the radio. By the age of 10, Nate had written his first original song.

But for much of his early life, his love of music would be overshadowed by his need to take part in meeting his family’s circumstances head-on. Nate’s father worked throughout the county performing farm labor and various odd jobs, and the sometimes feast-or-famine nature of his working life meant that his family would be forced to move from one rented home to another as money became scarce.

As a young child, Nate did his best to help the family situation, sometimes working in his time away from school shining shoes in downtown Cullman when he was just 7 years old.

In the 7th grade, Nate withdrew from Cullman’s school system to take any work that might supplement his family’s stability. He did stints working as much as possible on a milk truck — a job which began just after 3 a.m. each morning. He also worked toting fertilizer and doing any other odd jobs he could.

In 1953, Nate returned to his family home to a tragedy that would change his life. His older sister Ruth Persall was brutally beaten to death by a romantic partner with Nate’s own little league baseball bat which sat usually in the corner of the family home’s living room. Nate was the first to discover her body — he was just 13 years old.

The offender was quickly caught, jailed and later imprisoned after a short trial. But Nate told himself that one day he’d get revenge on the man who took his sister’s life.

Trending

In the years following his sister’s death, Nate found steady employment at a local Cullman supermarket and spent his off hours playing guitar and singing at events throughout the county. His original songs began to become locally renowned as he reached his later teens and early twenties, and it wasn’t an odd occurrence for Harvell to receive original song requests wherever he played locally.

At the age of 18, Harvell was baptized and saved at a church revival event held in rural Cullman County. Accepting Jesus Christ into his heart that day, Harvell would tell family later in his life, came with a spiritual mandate the young man wasn’t immediately certain he’d be able to keep.

As he reflected on the love and forgiveness provided through his promise to follow Christ’s path, Harvell said he felt God tell him that he must forgive his sister’s killer— and more still, he was instructed to love the evil perpetrator once he’d forgiven him.

Despite his local musical success and renewed faith, Harvell had a sense that accomplishing his life’s larger goals would require venturing away from his hometown and getting a look at the rest of the world. Meanwhile, the United States Armed Forces had a growing need for young men willing to do so.

Harvell joined the United States Navy in 1962 as a 22-year-old recruit, spending the next three years serving his country on ships touring various international strategic waters. Between jaunts in the Mediterranean, Europe, and Africa, Harvell’s love of music remained. He joined the Navy Band, which allowed him to stay connected to his musical passions while fulfilling what he saw as a worthy civic duty.

By the time Harvell was honorably discharged in 1965, the United States had begun to tumble headlong into what would eventually become a full-blown National identity crisis inflamed by social and political tensions.

Despite the tumult of the age, Harvell returned to Cullman in the mid-1960s, determined to fulfill a promise he’d made to himself as a young man just before joining the Navy. In an interview recorded circa 2018, Harvell remembered looking out the window of his family’s home at the age of 16 to see his mother using a broken broomstick to dig discarded coal from a rubbish heap in a neighboring yard. Her efforts would provide the only heat for her family’s home on a usually cold day. At that moment, Harvell said he made a personal vow that another member of his family would never endure the hardships he’d witnessed.

The young Cullman native took an entry-level position at a Monsanto Chemical facility in Decatur, Alabama, spending around a decade working by day—and saving money and honing his musical talents by night. He eventually cultivated local relationships that would contribute to his later success in both business and music.

It was also during this period that Harvell’s mother fell ill with cancer. After a lengthy battle with cancer, she passed away in 1968 weighing only forty-five pounds. Despite the toll his mother’s death took on him, Harvell was quickly forced to shove his grief aside and focus on caring for his remaining family including his niece Carol Jonsey.

After years of saving his plant paychecks and building upon the advice of movers and shakers who’d preceded him in the area, a series of small investment successes provided Harvell enough financial stability to return focus to his original dream career in music.

Harvell, who’d always been a country fan, set his sights on Nashville.

By this time country music was slowly moving away from the clean-cut crooners who had dominated turntables and radio waves throughout the 1940s and 1950s building the rhinestone foundation upon which so many later country superstars would tip their hats to sold-out crowds.

Following the televised assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, The United States’ subsequent escalated involvement in a widely debated conflict in Vietnam and the cascading national discomfort that ensued followed by a controversial 1968 Presidential contest, American trust in the Nation’s most powerful and enduring institutions was faltering in ways unfathomable to Americans at large mere decades prior. By 1974, which brought about the culmination of Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal, Americans had witnessed one President murdered on live television and another publicly ruined and run out of office—all in just over a decade.

In their 1985 hit “Are The Good Times Really Over,” country legends George Jones and Merle Haggard reflected on changed national attitudes brought on by the events of that period, singing, “I wish a buck was still silver; and it was back when the country was strong, back before Elvis and before the Vietnam War came along … And it was back before Nixon lied to us all on TV… Are the good times really over for good?”

Many country music fans consider the late 1970s and early 1980s as a Golden Age for the Nashville sound. And few regular folks had a better seat for the shift in the Nation’s zeitgeist which helped to bring about that Golden Age than Harvell. The young dreamer’s good times were only just beginning.

“I didn’t make it on my first try,” Harvell would later recount, adding, “I didn’t make it on my ninth try … but I was determined never to quit until I made it—and eventually I made it.”

In 1976, RCA Records’ Wanted! The Outlaws— a compilation album featuring previously released hits by Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Jessie Colter, and Tompall Glasser— was making history as the first country album to achieve platinum-certified success and selling upwards of a million copies.

Country music’s “outlaw” moment was in full force. The outlaws offered country fans a full-toothed response to the edgy rock music born from changing societal attitudes throughout the 1960s. The movement also provided a vehicle for many of the genre’s biggest stars to artistically protest what they deemed a stuffy and overly conservative image pushed by country record executives who’d built success on the backs of clean-cut crooners popular in the preceding decades.

After traveling to Nashville, Harvell’s motto of never quitting was key to the success he would later enjoy in the competitive country music capital. He attended shows throughout the city and introduced his self-written catalogue of country sound to anyone willing to listen. Eventually, Harvell became known in Nashville for the same tenacity and positivity he’d leveraged to build his early business successes back home.

It was also in the middle 1970s that Hank Williams Jr., a man born into country music royalty as the son of Hank Williams, famously made the artistic decision to rethink his place in his own “Family Tradition.”

According to his website, the younger Williams moved to Cullman after an eye-opening personal low in the early 1970s which included a drug and drink attempt to take his own life. During his time in Cullman beginning around 1974, Williams says on his website that he recorded his first “truly original work” after years of performing his father’s well-known hits all over the country. The 1976 “Hank Williams Jr. and Friends” album is widely lauded by critics as the true launching point for the younger Williams’ major success as a country music star in his own right.

Harvell’s artistic ambitions and Williams’ relocation to Cullman saw the two cross paths; and, for a time, the business aspects of both men’s artistic endeavors were managed by Cullman resident James R. Smith, who remains known today among members of the community for his eponymous association with an enduring trucking business still operating in the area.

Harvell joined Williams and other country music superstars as a studio musician on various projects throughout the 1970s, traveling between Cullman, Nashville, and the Tennessee River record town of Muscle Shoals to lend his voice, guitar, and bass playing skills to the recordings of multiple well-known country albums. And his famous friends would return the favor from time to time.

Harvell was signed to Republic Records, a label created and operated by “original singing cowboy” Gene Autry from the 1950s until the label dissolved at the closure of the 1970’s. A 1976 pressing from Republic included two singles self-written by Harvell with the help of legendary Nashville songwriter Don Pfrimmer. On each of those singles, “Wine and Weakness” and “If You Think You’re Ready”, Williams is credited as accompaniment, playing dobro to Harvell’s crooning.

While Harvell’s close relationship to the Nashville outlaw country movement was strong, he maintained a clean-shaven appearance after country superstars like Williams, Jennings, and Nelson had long since traded the bald faces and tidy suits of their childhood inspirations for beards, cowboy hats, and the drinking songs of love, regret, rebellion, and redemption which defined the outlaw era.

As Harvell continued to build his musical profile among Nashville’s biggest stars, his songwriting and stage presence incorporated elements of the popular outlaw trend while remaining heavily rooted in the influence of the smooth ballad country singers of bygone days.

It was, perhaps, due in part to his balanced approach that Harvell was offered a chance to record a country music rendition of Lionel Richie’s famous “Three Times a Lady.” The hit song, played with a country sound, begged more classic crooning than it did outlaw cantankerousness. Harvell’s version of that song, which Richie and The Commodores would go on to make one of the biggest pop music hits of the century, took the Nashville aspirant to the top of the country music charts for several months in 1978. Harvell’s country version of the song hit the airwaves two weeks before Richie’s pop version. In October of that year, Harvell was recognized by the American Association of Composers, Authors, and Publishers for his chart-topping success, receiving awards for his hit.

By that time, Harvell had written more than a hundred songs and released a handful of albums through Republic with varying degrees of success.

In a 1978 interview published in The Cullman Times, Harvell credited much of his musical success in Nashville to the encouragement of local friends and support from the community he would always call home.

“Of course, there were disappointments along the way,” he said. “…But I know there was a reason… You get on to the next chapter thinking you get them the next time.”

Harvell’s next chapter began with his return to his hometown in the early 1980s after considering what a lifelong dedication to remaining relevant in the ever-changing music industry would mean for his ability to focus on his faith and the family he wished to build.

According to conversations he had with family members, Harvell was attending a music industry event in the late 1970s when he overheard an already “made” country star remark that he’d trade his success immediately for the moments he’d missed watching his young children grow into the world.

The Nashville music industry’s thirst for artists’ unyielding willingness to sacrifice all for acclaim was a topic Harvell had noted in “Another Worn Out Rhinestone”, a song he recorded before his overnight fame as a hit-singer.

In that song, Harvell sings of a man making his way home on Interstate 65, the main thoroughfare connecting his own childhood home to the city where he’d found country stardom, worn out by endless demands from industry executives and all-night bookings on stage.

“I-65, trucks blowing by, windy hair stinging on my face. Live and learn, give and burn—but I won’t be caught dead singing in this place,” Harvell sings, continuing, “Maybe Kris (Kristofferson) cleaned ice trays—but I think I cleaned their stool. Dreams give way to hunger and the starving man’s a fool.”

Later in the song, Harvell reveals that the hunger so many artists attempt to satiate with fame and fortune had already been filled in his early life through faith.

“God, are you still there like someone said?” Harvell asks in song, “Well, according to me… you must be, because there’s fifty Gospel songs running through my head.”

“And another worn-out rhinestone just fell off and hit the ground,” rings the song’s chorus as Harvell’s star makes his way home.

Following his Nashville success, however, Harvell’s shedding of a few rhinestones was never viewed personally as a step backward.

Upon his return to Cullman, Harvell continued to nurture the investments and business opportunities that had given him an initial boost to pursue his artistic ambitions. And soon it became apparent that his knack for business remained strong.

So too did his faith. In the years following his sister’s senseless murder, Harvell never forgot the promise he made to leave behind any thought of vengeance in return for his promise of Heavenly salvation. After the killer was granted an early pardon and returned to Cullman, Harvell told family members he came face-to-face with the man who’d caused him so much childhood pain early one morning in a local diner. Harvell and the man spoke over coffee. The encounter ended with Harvell telling the man that not only had he forgiven him but also that he loved him.

In the late 1980s, Harvell met April Gaw in Cullman and the two were married. In 1989, they welcomed their son Nathan Harvell into the world.

For the next several years, the elder Harvell focused his efforts on building a business fulfilling community needs in housing, commercial development, and local entertainment. He became well known and respected throughout the community for his willingness to afford others the same benefit of wisdom he’d received from early mentors to his successes.

But for Harvell, there were more challenges in store.

Eventually, a series of business realities and personal challenges in the 1990’s led to difficulties which culminated in Harvell having to restructure his business and begin again—almost from scratch.

Following a divorce, Harvell and Gaw remained close and continued to spiritually support one another while, according to their son, co-parenting before the term had become a part of the modern lexicon.

“I remember my Dad telling me there was a time when he was struggling in business and with some serious health difficulties that had him depressed,” the younger Harvell said in a recent interview, “And my Mom reminded him he needed to read his Bible.

“He said he opened it to Psalm 125, read it,” Harvell continued. “And never worried again for the next 30 years. And I saw that peace in him as an inspiration.”

The passage reminds the faithful to remain steadfast in trusting God, saying in part: “They that trust in the Lord shall be as mount Zion, which cannot be removed but abideth forever.

“As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about his people from henceforth even forever.”

Harvell eventually found renewed stability in his entrepreneurial endeavors and never really retired, remaining active in his business and community relationships until his final days.

“Dad never met a stranger, “said son Nathan. “And anybody you talk to who knew him will tell you his favorite thing was to pass on wisdom and encouragement to anyone in need of a push toward their own goals.

“He wanted to see people happy and knowing that their dreams were way closer in reach than they might think.”

One person Harvell loved seeing happy the most is his granddaughter, 5-year-old Ava Harvell, to whom he will always be known as Poppy.

And Harvell’s motto of “never quit” will live on, his son said, adding that he’ll be sure his own daughter grows up understanding the power of encouragement behind those two simple words.

“Dad’s legacy will live on,” his son said. “And he will truly be missed by many.”

Harvell’s family and friends gathered for a visitation and funeral at Moss Service Funeral Home celebrating Harvell’s life on Sunday, March 2, 2025. Harvell passed away peacefully surrounded by family the previous week following a short illness at the age of 84.