Five-day wait for mental health bed not uncommon in Iowa

Published 12:02 pm Friday, May 12, 2017

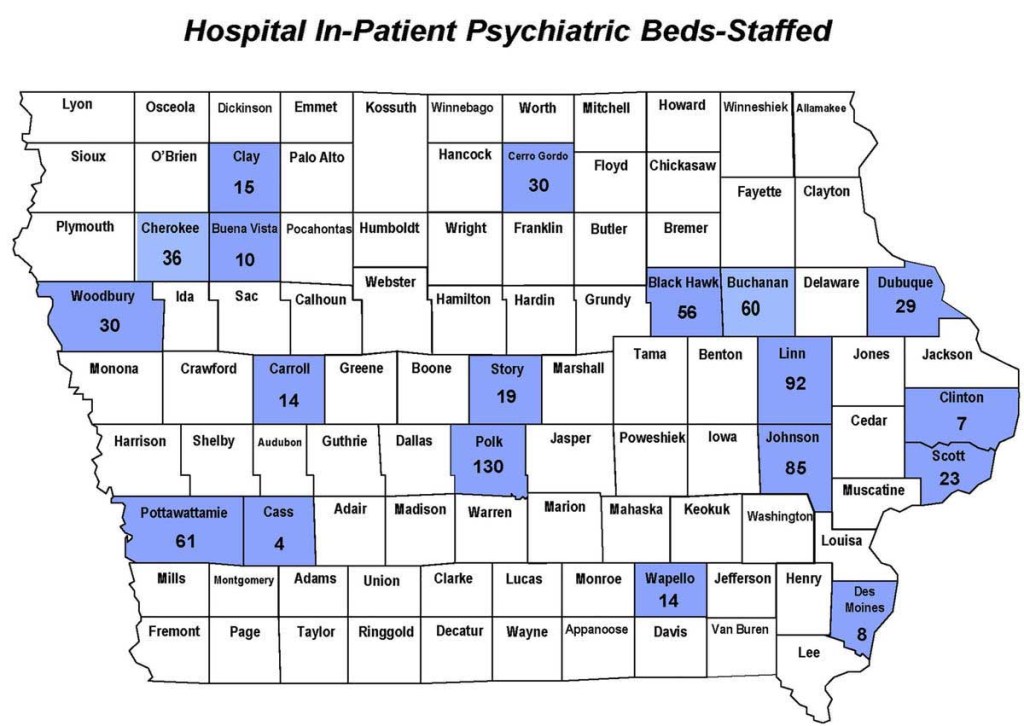

- Mental Health and Disabilities map of the inpatient psychiatric hospital beds in Iowa.

KNOXVILLE, Iowa –– When someone has a heart attack, treatment is immediate. When someone has a mental health crisis, there’s a waiting list.

Those are the sentiments that are routinely expressed by the sheriff, public health officials, area hospitals and those that have battled with a mental health diagnosis.

Trending

It’s an issue noted by many in the state of Iowa. Marion County faces it just as much as everywhere else, according to dozens of local officials and mental health sufferers interviewed during a monthlong investigation by Iowa newspapers, the Journal-Express and Pella Chronicle.

There’s enough beds in the state, says Gov. Terry Branstad. That’s not so, says Marion County Sheriff Jason Sandholdt.

“When people say there’s enough beds in the state of Iowa, they’re crazy,” Sandholdt said. “There’s not enough beds for that 32-year-old, intoxicated person that has bipolar or schizophrenic episodes, and they’re wanting to hurt themselves or hurt someone else. There’s not enough beds available.”

Instead, that 32-year-old would have to wait for a bed. Sometimes the wait is a few hours, sometimes it’s days.

“We’ve had people here up to five days,” said Kellie Jones, the emergency room coordinator at Knoxville Hospitals & Clinics.

Jones and the emergency department has to deal with these issues several times a week. The resources to treat those in a severe mental illness crisis aren’t available in person at either Marion County hospital, Knoxville or Pella.

Trending

Patients presenting a mental illness check in at a local emergency room, sometimes brought there by law enforcement, while others come by themselves or with family.

In Pella and Knoxville, they are assessed by an in-house social worker or counselor, and can also be assessed by a Skype-like service referred to as “telepsych” or “telehealth” to see a psychiatrist.

At that point, a diagnosis will be made. Sometimes, it’s a change in medication. Others will be referred to either an outpatient or inpatient clinic.

For those being referred to inpatient facilities in a serious mental health crisis, often times they will find themselves in an ER room for days. There are no inpatient facilities for mental health in Marion County.

“It’s called emergency boarding,” said Jean Holthaus, the clinic manager of Pine Rest Christian Mental Health Services in Pella. “We end up boarding people in the emergency room for days at a time sometimes, because we can’t find an open bed.

“So then, some of our social workers and nurses at Pella Regional Health Center end up calling every inpatient unit and saying, ‘Do you have a bed available?’ If they don’t, they call back the next day. They have to wait until someone is discharged before they can be admitted.”

During that waiting period the hospitals keep them comfortable with a place to sleep, and food. But psychiatric treatment is put off until a bed is found.

“They’re just laying here, and we’re not doing anything,” Jones said. “It’s sad. I feel bad for them, because nothing is happening to help them.”

While boarded patients wait for a bed, all the hospital staff can do is keep them safe.

“They’re just keeping them safe, basically,” Holthaus said. “They’re in a room until they can get a bed for them. But no, they’re not treating them because they’re not equipped to treat them. It’s outside the scope of their practice. So people basically end up sitting and waiting to get treatment.”

The state of Iowa, according to data from the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center, has 64 state operated beds, down from 149 in 2010.

Iowa lost 83 state beds in 2015 when Iowa governor, Terry Branstad vetoed funding set aside for two state-run institutions. Branstad was sued by a group of legislators and an employer union. They argued that state law mandated a mental health institution in each corner of the state. The Iowa Supreme Court ruled against that argument in 2016.

Peggy Huppert, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Iowa office, said she disagrees with the notion the state-run facilities closed were outdated.

“We dispute what he has to say about he is ‘modernizing the mental health system.’” Huppert said. “That implies that the facilities in Mount Pleasant and Clarinda were not modern. When, in fact, they were and very good care was provided in both of those places.”

Instead, she says, the state made it harder and harder for the facilities to survive financially, lessening the beds time and time again. And when they were closed in 2015, she said, this allowed them to brush it off like it wasn’t a big deal.

“If you really dig down, you find the real reason or the real objection to having those facilities open is the cost,” Huppert said. “And he has talked about that, how that was just too much money. But part of the reason for that is they kept reducing the number of beds over a period of years at those institutions…so that they could essentially starve them, and then say, ‘Oh, well it’s no big deal. We’re closing them, and they don’t have that many beds.’”

Last year, Branstad’s office put out a press release citing a report from Mental Health America, a nonprofit advocacy group that named Iowa was a top-10 state for mental health care. In a statement, he said then that the state’s bed-tracking system showed between 60-100 beds available at any point in name.

The question isn’t necessarily how many beds are open, Huppert said, it’s what kinds of patients those open beds will accept.

“You have to look at who needs the beds, and what kind of beds are there,” Huppert said.

In Iowa, mental illness often isn’t alone. Huppert said there are a percentage of Iowans that along with their mental illness may have a substance abuse issue, a developmental disability or a history of violence. These are considered patients with “complex needs” and since open beds aren’t required to take a patient, finding a bed becomes a challenge.

“There may well be 60 beds available,” Huppert said. “But none of those places is going to take the people who actually need the beds. So there’s a mismatch between the people who need the treatment and the beds, and the kinds of beds available.”

Huppert added that roughly 50 percent of those with mental illness, also have a substance abuse addiction to go with it.

“It’s a very common thing,” Huppert said.

She added that state formally had a mental institution that had beds specifically for these individuals. That was Mount Pleasant, which was closed in 2015.

There are 29 hospitals that have psychiatric beds in the state, according to the latest available 2016 data from the Iowa Department and Human Services. There are 802 beds licensed around the state, but of those 731 are staffed. A total of 489 are available specifically for adults.

Since that data was collected at least eight of those beds have been closed. Last month, the Mahaska Health Partnership hospital in Oskaloosa closed all eight beds in its inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to a map provided by Iowa DHS, there are roughly 160 psychiatric beds within 50 miles of Marion County. The rest of the beds are located in the eastern and western ends of the state.

MORE BEDS STIFLED BY PRIVATE HOSPITALS

Last year a state board had a tie vote not once, but twice, on whether or not to allow a company to build a 72-bed mental health institution in Scott County. Each of the 72 beds would have been certified as acute beds, able to house the most severe cases of mental health crises.

The State Health Facilities Council has a process referred to as the “Certificate of Need.” Major renovations or a new project valued above $1.5 million must be approved by a majority vote.

Officials with Strategic Behavioral Health, the Tennessee company trying to build the institution in Bettendorf, twice met in front of the board to seek the go-ahead for their project. They were never able to see the full board, and both times the vote ended in a tie. While a tie vote was not a denial, it was essentially akin to the board tabeling the item.

Mike Garone, director of development for Strategic Behavioral Health, told the Journal-Express and Pella Chronicle that the company will decide soon on whether they will give it a third shot. Because of this, Garone couldn’t comment specifically on the project, but he did share the thoughts behind what drew the company’s interest to Iowa.

When determining whether or not to enter a new market, Garone said the company studies the market. They determine things such as community perception to a facility and the number of beds available in the area, and how often they are used.

“We went into the market and everything was looking good,” Garone said. “From our data, from our research and from the confirmation of stakeholder meetings and the support that we’d gathered.”

Things changed once the project came to the State Health Facilities Council for the go-ahead. Two area private hospitals — Genesis Health System and Unity Point — objected. They say the capacity offered by their two systems alone is enough for the region that covers five counties. Genesis said the issue is not beds, but rather a shortage of psychiatrists.

Huppert said overall, it’s a case of two differing stories, with the truth lying in the middle.

“As if often the case with two sides that have disputing positions, the truth is somewhere in the middle,” she said. “I know that Genesis has said that they have plenty of capacity, that there is a provider shortage. Which, I agree, there is a provider shortage. But, on the other hand, when you’re willing to pay enough you can get the providers. Broadlawns [Hospital in Des Moines] has just gone through that. They’ve procured a whole new crop of psychologists and psychiatrists because they pay them.”

PROBLEMS CONTINUE ONCE BED IS FOUND

Finding a bed is only half the battle for patients in a mental health crisis. More often than not, the free beds are in the far corners of the state. The most-often used facility for Marion County court committals in the last fiscal year was Council Bluffs. The next-highest was Des Moines with 17, but 13 other patients went to Cedar Rapids, and others were scattered around to other places such as Davenport, Mason City and Iowa City.

“There’s a lot of times where deputies are passing each other,” Sandholdt said. “That someone from northwest Iowa would be taking somebody to southeast Iowa to a hospital, we’re taking somebody to northwest Iowa.”

It’s not a glamorous ride, either. After waiting in an ER for somewhere between a couple of hours or a couple of days, it can be a trip of anywhere from one hour to seven or eight hours, depending on the circumstances. And that trip isn’t in an ambulance, it’s in the back of a police car.

“It’s humiliating,” Garone said. “It’s an illness. If we were putting individuals that were suffering from any other health condition in the back of a squad car, there would probably be a civil rights outcry.”

“If we had a laboring mother,” Garone continued, “and there wasn’t services in her community and she wasn’t able to deliver her baby in her community, and we put a laboring mother in the back of a cop car and drove her eight hours away. Literally, there would be a march on the Capitol. There would be people on the Capitol steps demanding justice. Why doesn’t a mental health patient deserve that same respect? I just don’t understand it.”

The county bears most of the expense to transport patients to and from these far away inpatient facilities.

“Our sheriff’s department is having to transport someone from Marion County to Council Bluffs to the hospital,” said Angela Nelson, disability service coordinator for the CROSS Mental Health Region. “Sheriff comes back, then that person is seen for a hearing, sheriff has to go pick them up, bring them back to the hearing. And, sometimes, take them back to the hospital if they need to go back.

“So, not real convenient when we only have a couple of hospitals that are taking patients.”

MENTAL HEALTH NOT A MONEYMAKER

If there is such a need for beds, why don’t hospitals and companies just build them everywhere? The answer may be because mental health care isn’t necessarily profitable, especially if done on a small scale. Insurance companies offer minimal reimbursements when compared to other medical conditions, and Medicaid can offer even less.

Holthaus said a hospital or provider couldn’t just put up a few beds in Marion County and sustain those services. She estimated a minimum would be a roughly 12-bed facility, but that extends beyond the need for Pella and the area.

“You can’t really have a psychiatric unit that has four beds in it,” Holthaus said. “You’d need to be a minimum of 12 to make it float because of all the resources they have around [them].”

There are other requirements, Holthaus said, that make local facilities hard to create.

“You have to have a psychiatrist, you have to have all these regulations that go around having the unit,” Holthaus said. “And, it’s one of those specialties the reimbursement is at the lowest rate. So then, it’s hard to make money off of it, given all the things you have to have there.”

Waiting with patients in the ER can be costly, as well. Knoxville Hospitals & Clinics spends roughly $70,000-$100,000 each year to bring in additional staffing in the ER just to monitor mental health patients while they wait for a bed, according to data from the hospital. Overall, the hospital reports losing roughly $200,000 annually for unreimbursed medical expenses relating to mental health.

Pella Regional Health center estimated they provided more than $750,000 in patient financial assistance, but they were not able to pinpoint how much was given to mental health care. PRHC determines financial assistance based on whether the patient qualifies for financial assistance, not based on their diagnosis.

The Medicaid reimbursement rate is one thing, getting paid through the newly privatized Medicaid system in Iowa has become another. Now, instead of Medicaid paying claims, a managed care organization, or MCO, is the one reimbursing. Their payments haven’t always been timely, officials say.

“Medicaid, the reimbursement is horrible,” Kim Dorn, director of Marion County Public Health, said. “And getting paid by the MCOs over this last year has been a really big problem for providers. And there have been providers that have gone out of business because they didn’t get paid by the MCOs.”

Ocker and Presley write for the Knoxville, Iowa Journal Express.