Cnhi Network

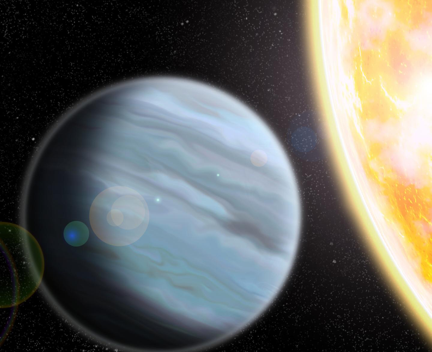

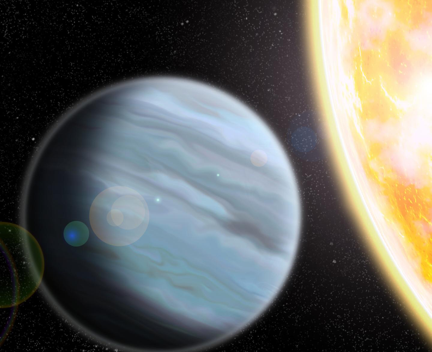

Styrofoam-like planet catches astronomers’ eyes as testbed

A newly discovered exoplanet with the puffy density of styrofoam may become a testing ground for learning to ... Read more

A newly discovered exoplanet with the puffy density of styrofoam may become a testing ground for learning to ... Read more

A newly discovered exoplanet with the puffy density of styrofoam may become a testing ground for learning to ... Read more

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — For the first time ever, astronomers have discovered seven Earth-size planets orbiting a nearby ... Read more

On Valentine's Day 1990, from a dark and frozen spot on the outer edges of our solar system, ... Read more

So-called hot Jupiters — exoplanets that are basically like Jupiter, but hotter — have often seemed to have ... Read more