Ringside seat: Cullman native Michael D. Waters publishes new reflections on key role in Gov. Fob James’ first term

Published 5:15 am Wednesday, January 5, 2022

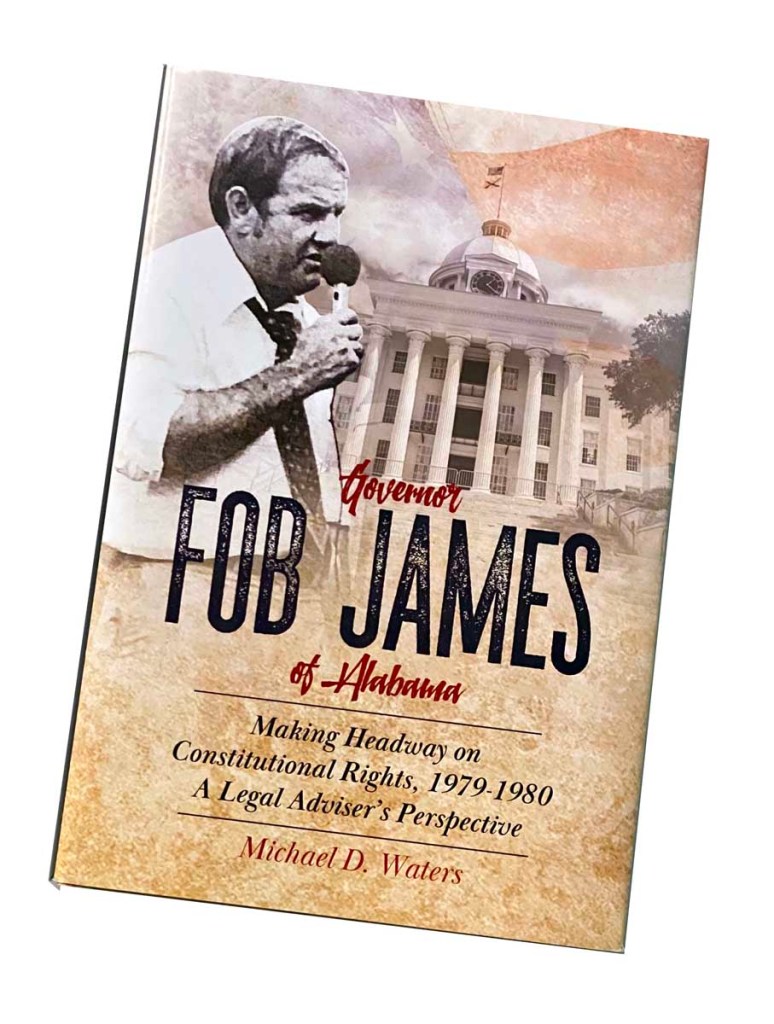

- Book Cover

Fob James’ first term as Alabama governor came in the wake of decades of lopsided political consolidation in Montgomery. George and Lurleen Wallace dominated the governing culture in Montgomery throughout the 1960s and 1970s (with a single-term stint from Albert Brewer in between), making James’ early days in the governor’s mansion an exercise in redefining expectations for how his office would get along with the legislature.

It’s a lot to revisit — even before regarding James’ 1990s comeback as an elected Republican governor. But as James’ first-term legal advisor, Cullman native and longtime Birmingham-based attorney Michael D. Waters, had a front-row seat as James attempted to craft alliances that could enact his ambitious goals for prison and constitutional reform. Now he’s released a book that reflects on that experience. It’s a mouthful of a title, but it’s a firsthand glimpse into James’ early efforts at making often tumultuous headway in a governing environment that, for better and for worse, had become politically ossified long before he took office.

Governor Fob James of Alabama: Making Headway on Constitutional Rights, 1979-1980 — a Legal Advisor’s Perspective released in September of last year (with a portion of the sales proceeds going to St. Bernard Abbey), and in a recent email Q&A with The Times, Water said he did his best to deliver on the title’s promise.

Here’s a sampling of Waters’ thoughts on James’ frustrated efforts to address a pair of perennially challenging goals — goals that in 2022 continue to evade most state politicians’ list of top priorities: rewriting the famously labyrinthine and lengthy Alabama Constitution of 1901, and enacting a program of prison reform that keeps the state free from the watchful eye of the federal courts.

The Cullman Times:

Whom is this book for? A general readership interested in behind-the-scenes political history? Alabama history buffs? People interested in public policy at the state gov’t level? Others?

Michael D. Waters: Not to be too broad, but the book is for any of the persons listed. Certain persons interested in how the governor’s office works may find it useful. I tried to provide some views about the practical issues that come up and also “demystify” the office in that public officials are doing their daily tasks and attempting to solve problems, as anyone might do at work. The key here, however, is that the work, and the solutions, can affect everyone in the state. Fob James believed that.

Certainly, Alabama history buffs may find it helpful, as may people interested in public policy. I have sent the book to a number of friends and colleagues around the country, and have had responses from some stating that the issues covered in the book seem to apply to where they are located.

The Times: How would you characterize Gov. James’ personal conviction, behind the scenes, about the two big topics you identify (constitutional and prison reform) as his major first-term priorities?

MDW: One thing about Gov. James that I tried to make clear in the book is that he was dedicated to pursuing what he believed to be in the interest of the citizens and he was not interested in personal advancement. He certainly believed that about constitutional reform and prison reform. On the constitution, he believed (correctly) that the constitution of 1901 hindered the ability of local governments to deal with local issues and he wanted to correct that. However, providing more flexibility to local governments to deal with local issues took away authority from the state legislature, and, thus, made the passage of a new constitution a major political task. The governor’s proposal passed the senate but not the house. After failure in the house, the governor backed off of the promotion of constitutional reform because he saw that the politics of the legislature would not approve a new constitution.

On prisons, he worked hard throughout his first term to correct the many problems in the state’s prisons: overcrowding, overcrowding in local jails, lack of inmate reform and rehabilitation, and inmate violence. He strongly believed that inmates who could be rehabilitated should be and, if they were, they would be productive back in society. The book points out that a major roadblock to building new prisons was the St. Clair County opposition led by its county commission chairman, and getting the new prison started there was delayed by more than a year due to the court proceedings that were necessary to obtain clearance to start the new prison.

The Times: Gov. James followed nearly two decades of a political culture dominated by Gov. Wallace. Does the book describe what it felt like to be part of an administration that must have had to create its own new culture? Was there a sense of disruption or of setting new State House norms, in terms of the way the governor’s office related to the legislature?

MDW: Following the two decades of the Wallace influence was a major task, in that the governor believed that day-to-day problems in the state needed major reform. Those problems included, in addition to constitutional reform and prison reform, enhancing the state’s primary and secondary education, budget control, proper management of state funds, and mental health reform. But because Fob James was not a “politician,” and because he brought a number of new people to join his staff, there was some resentment, particularly in the legislature, to the governor’s approach. He did not believe in “playing politics” to get things done and that, of course, made a number of politicians annoyed at their lack of influence in the governor’s office.

The Times: In 2021, prisons in Alabama are still a big deal. The constitution may be too, though it’s hard to get a current representative or senator to talk about that with any political urgency. Do you think a governor’s office that takes point in prioritizing those kind of politically ambitious issues before the legislature can make much of a difference in actually getting substantive legislation to move on them?

MDW: You are correct, politicians don’t much like to discuss constitutional reform or prisons. On the constitution, there are so many issues that are dealt with in the constitution, like the earmarking of tax money for certain education issues (which the Alabama Education Association would oppose revising), the cap on property tax (which large landowners would oppose lifting), the continued authority in the legislature over local issues (which most legislators would oppose lifting). All mean that any effort to obtain substantial constitutional reform would not likely be supported either by large lobbyists or the legislature as a whole.

On prisons, legislators and politicians generally do not like to talk about prison reform because no one wants to be accused of being “soft on crime.” The desire to “punish” is prevalent. Yet, the current overcrowding within the state’s prison system, the lack of inmate rehabilitation, and the prevalence of inmate-on-inmate violence all harm every citizen in the state. Overcrowding leads to the need for more, larger prisons, which is a huge drain on the state’s finances. That drain takes money away from other projects like roads, bridges, schools, industry promotion — all projects which benefit everyone in the state. The lack of inmate rehabilitation and inmate violence mean that, when an inmate is released after serving a term, the inmate often goes back to what he/she is used to: further crime as a “repeat offender.” That means that the lives and property of every citizen in the state are in jeopardy. Overlooking the need for prison reform is like shooting oneself in the foot.

The Times: You’re a Cullman native? Can you give a brief rundown of your past and/or current connections to the Cullman area, in order to orient our readers?

MDW: I was born in Cullman and graduated from Cullman High School in 1968. My dad grew up on a farm just north of Hanceville and was a radio announcer at WFMH Radio here in town. He was in the Army in WWII in New Guinea, and then after the war joined the reserves. The reserves were called up for the Korean War, and while in training to be sent to Korea, he was in a car wreck, broke his back, and was paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of his life. That did not deter him much — he drove his car to work every day using hand controls.

My mother grew up in Cullman. Her father, Peter Geisen, was a blacksmith in Cullman and had only a 4th grade education. My sister, Sondra Nassetta and her husband Pete, live in Cullman, and my nephew, David Nassetta, is on the Cullman police force. The current Abbot at St. Bernard, Marcus Voss, is a cousin. I married Brenda Howell in 2019 and moved back to Cullman, while still practicing law in Birmingham. Brenda spent her career in Cullman as chief of juvenile services for Cullman County, and she served four terms on the Cullman City School Board. My son-in-law, Nathan Anderson, is the head of Cullman Parks and Recreation.

Published by Homewood-based Rocky Heights Print and Binding, Governor Fob James of Alabama: Making Headway on Constitutional Rights, 1979-1980 — a Legal Advisor’s Perspective is available online at the Book Nook, Rocky Heights’ web-based storefront for regionally-published authors. Visit the Book Nook and find your copy online at www.localbooknook.com.