Alabama’s hidden history: How highway could fuel tourism

Published 1:55 pm Sunday, March 21, 2021

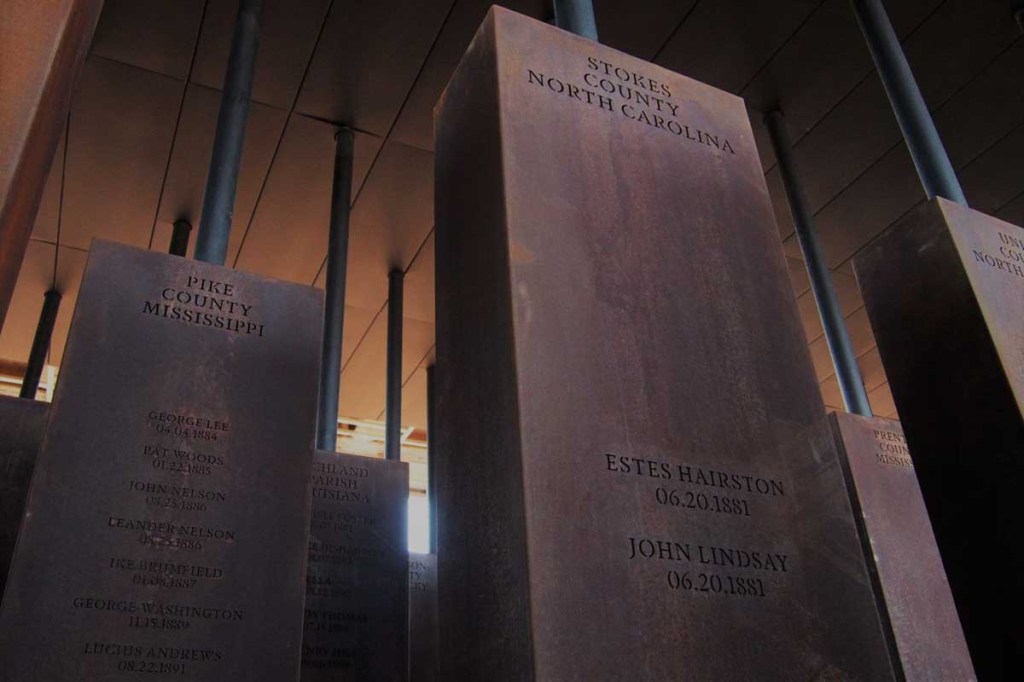

- More than 800 six-foot steel monuments hang in the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. They are meant to suggest the tragic and unjust end that befell about 4,400 people from 1877 to 1950. Each monument represents a county where a documented lynching occurred.

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — During a killing spree in Greene County 150 years ago, a mob of Klansmen on horses murdered a Black political leader and a white politician.

Seven months later, in October 1870, a massacre at a Black political rally in downtown Eutaw left dozens wounded and four dead. Blacks feared for their safety and stayed home during that November’s elections. Alabama’s brief flirtation with the promises of Reconstruction ended.

The horrifying history received national attention last month in an Atlantic Magazine story entitled, “A Riot in Eutaw,” as part of “Inheritance,” a project about American history and Black life. It’s the type of history that is hidden in Eutaw, where there are no notable historical markers or museums dedicated to a painful moment in history. But it’s an example of a harrowing tale that is getting more of a reckoning in Alabama and elsewhere in the Deep South.

With the prospects of adding a four-lane U.S. 43 corridor moving forward, there is some belief that opportunity awaits to awaken stories long forgotten.

“I think there is a way in which a transportation official can imagine more of an obligation to bring traffic, or at least information about the past to the road they are building,” said John Giggie, director of the Summersell Center for the Study of the South at the University of Alabama. “Places like Eutaw and Demopolis have a rich history in the civil rights era and are not told right because access to them is off the beaten path. I see no reason why these roads can’t be built with the ambition of, ‘can we enliven the historical past?'”

The Alabama Department of Transportation could play a role as the project moves forward. ALDOT, according to spokesman Tony Harris, would “entertain discussions” regarding wayfinding signs to historic sites, though he added there “are some guidelines on what can be signed for, but it’s not uncommon to do that.”

FEDERAL DESIGNATION

The timing of the massive public infrastructure project comes as the South has seen a surge in post-Civil War Jim Crow-era tourism. Research completed in 2016, showed that 68% of Black travelers would like to learn more about Black history and culture while traveling.

In Montgomery, the birthplace of the civil rights movement, the national “lynching museum” is drew large crowds before the COVID-19 pandemic and international acclaim since its opening three years ago.

In Mobile, city officials are hopeful that the 2019 discovery of the slave ship Clotilda will lure visitors to the Africatown community where plans are underway for a new museum, welcome center, and water tours. Birmingham is home to the National Civil Rights Institute, and Selma has seen a rise in tourists.

In the Black Belt region, Tina Jones is looking for guidance from federal lawmakers as they covet a designation from the National Parks Service for the Black Belt region to become Alabama’s second federally designated heritage area. The only Alabama heritage site recognized by the National Parks Service is in the Tennessee River basin and encompasses Muscle Shoals and Florence. There are about 50 of them in the U.S.

Federal legislation, backed by U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell, D-Birmingham, could be adopted later this year that designates 19 counties in the Black Belt as a national heritage area. Proponents say the effort would be utilized as a marketing and branding tool for bolstering tourism.

Jones, president for the board of directors with the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation and the Alabama Black Belt Heritage Area, said the advantage of the designation would be in a branding opportunity linked to the Parks Service. She said the region would benefit on additional expertise and assistance from the federal agency that comes along with the designation.

“We don’t have an official designation yet, but for the last 10 years we’ve acted like a heritage area in trying to piece these things together,” said Jones.

The designation would also provide a boost for the small communities in the Black Belt with histories that are often undersold compared to Selma and Montgomery. She said interpretative signage and audio tours are prevalent in some communities and are somewhat non-existent in others. She said Selma has 76 sites linked to the tours, Wilcox County has 104, Sumter County has 50 and Monroeville has about 40.

“We would want to increase those things in the Black Belt and especially along Highway 43,” said Jones. “We would work to connect with the local communities and to think about what they would want to highlight.”

In Linden, that could include highlighting Lewis Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church where Mayor Gwendolyn Rogers said Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. held a rally in the early 60s. Linden is also the hometown to civil rights icon, Ralph Abernathy, a close King associate and co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. George P. Austin Junior High School, according to the mayor, was once an all-Black dormitory where students would stay during the week and attend school before returning on weekends to their families and farm.

Rogers, herself, created a bit of history last September when she became the first Black person ever elected mayor in Linden. The city has a population of less than 1,800, with 51% white residents and 46.7% Black, according to the last Census count over a decade ago.

“We are working hard to build up our city to where people will want to go through here and see some attractions in town,” said Rogers. “I remember my mother and father telling me the stories, those historical aspects. Dr. King did come here and speak. It’s definitely a potential.”

‘HIDDEN HISTORY’

But that history also includes raw brutality, which could prove difficult to unfurl. The Eutaw massacre is among those moments that could provide a spotlight on how Alabama’s foray with Reconstruction unraveled amid racial terrorism and the emergence of the Jim Crow South.

Bertis English, a professor of history at Alabama State University in Montgomery, said there are opportunities for national, state, and local politicians to “shed light on past injustices” throughout Alabama.

“Roadside markers are good,” said English. “Roadway names are great. How many officials wish to pursue either one of those two possibilities is the question.”

Challenges still exist in getting that history told. English said there was “considerable opposition” in the efforts by Bryan Stevenson in pursuing the lynching museum in Montgomery after his associates revealed their plans. Only when the full reflection of tourism dollars was projected, did “words from some mouths change. Even then, whether minds followed suit was questionable.”

English said the Alabama Historic Memorial Preservation Act, enacted in 2017, typifies the “depths to which certain Alabamians are willing to sink to keep visible as many physical remnants of white-dominate, not simply white-led, South.”

Despite the law, Alabama ranked No. 3 in the nation last year in removal of a dozen Confederate monuments. One of the monuments that remains received national attention in 2016, in Demopolis, after a police cruiser slammed into it and destroyed the Confederate soldier statue that long stood atop it. City officials, following extensive debate on the future of the structure, determined to replace the soldier statue with an obelisk inscribed to memorialize dead Confederate soldiers.

Giggie, the professor at the University of Alabama, said the challenge for state and local officials is whether they are interested in investing into truth-telling about its past.

“This is a hidden history,” said Giggie. “Part of (the reason it’s hidden) is because the physical infrastructure of travel in the 21st century doesn’t always take you there. That’s one step in creating that history, and when you get there, you need more stories and museums.”

‘LONG OVERDUE’

Wayne Flynt, an Alabama historian and professor emeritus at Auburn University, said the prospects of cultural tourism could provide a boost for one of the poorest regions in the state.

Though he is not a fan of transportation projects in general, Flynt said a widened U.S. 43 could “open up” a region that makes it more accessible to tourism and economic development.

“It is long overdue,” said Flynt. “Since the end of the Civil War, (the Black Belt region) has been in decline as Blacks moved away and economic opportunity slowly declined. Now they are the poorest places in America, mainly supporting outside-owned timber plantations. Health and education abound. Yet, the prospects of cultural tourism are enormous as are the indigenous crafts such as pottery making and gospel music, and other crafts on display at Black Belt Treasures in Camden, a gem of a tow but not easy to access or learn about.”

Flynt said the Black Belt region needs a north-south highway in the western part of Alabama that connects Memphis to Mobile, and a highway that moves west from Montgomery to Jackson, Mississippi.

“It is a beautiful drive with wonderful vistas, history and culture and could be a huge shot in the arm to the poorest part of Alabama,” he said.