50 years after SCOTUS ruled death penalty cruel and unusual, race factors heavily in executions

Published 11:26 am Tuesday, June 28, 2022

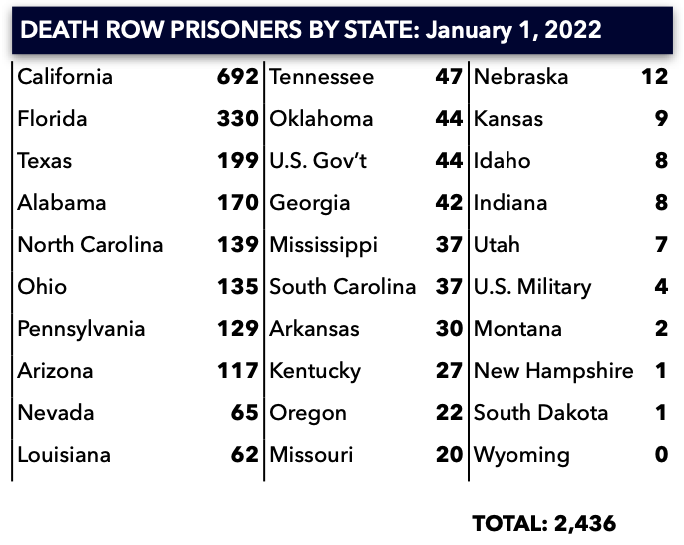

- Chart shows the number of death row prisoners by state as of Jan. 1, 2022 Graphic by Death Penalty Information Center

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional 50 years ago, but a mere four years later the Court reversed that decision.

In the 50 years since SCOTUS said the death penalty amounted to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of Eighth and 14th Amendments, more than 23 states have abolished execution as a form of punishment — 11 of them in the last 16 years.

The June 29, 1972, decision — halting executions in the country — was based on what the judges called legal arbitrariness, finding that capital punishment was often imposed discriminatorily and inconsistently.

That decision was the result of a challenge to a death sentence handed to a man named William Furman, a Black man who was burglarizing a home when he shot and killed a resident of the home. The Supreme Court case was coupled with two others, one from Georgia and another from Texas, in which the defendants were sentenced to death for rape.

The Court reinstated the death penalty in a 1976 decision that allowed states to revisit death penalty statutes if the sentence could be generally and uniformly applied.

“It is at least as arbitrary, if not more than it was at the time Furman was decided,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit that analyzes issues surrounding capital punishment.

Furman was burglarizing a private home when a family member discovered him. He attempted to flee, and in doing so tripped and fell. The defense said the gun that he was carrying went off and killed a resident of the home.

In Georgia, 400 death sentences have been imposed since Furman and 76 people have been executed.

“Of course, some people have died of natural causes and then some people are still on death row. But it shows you, I think, that the courts have taken very seriously that their duty to review death sentences and ensure that there are no errors in the case,” said Anna Arceneaux, executive director of Georgia Resource Center, a nonprofit law firm which provides representation to Georgians on death row.

In the last eight years, two people hav received the death sentence in Georgia — one of them, Tiffany Moss, a Black woman who represented herself in trial, was sentenced to death for starving her daughter to death and burning her body in Gwinnett County.

“One of the lessons of Furman and one of the reasons the court struck statutes down in 1972 was because the death penalty had become so arbitrary and capricious and unfortunately, 50 years later, that’s still true,” Arceneaux said. “The people who’ve received the death penalty in Georgia, the people who are still on Georgia’s death row, are not the worst of the worst. There are people who, had they committed the same crime in Fulton County or Cobb County, the prosecutors would never seek the death penalty against them. Race is still a major factor in how the death penalty is applied, geography and where you commit the crime and who’s the district attorney, and then sometimes the crime itself. But it still remains very arbitrary and discriminatory.”

Most recently, Ricky Dubose was sentenced to death this year in Georgia for killing two security guards in 2017; Brian Nichols, an inmate accused of killing four people in an Atlanta courthouse in 2005 and escaping afterward, did not get the death penalty.

“We have clients who were involved in a convenience store robbery in South Georgia, who may not have even pulled the trigger and they’re on death row, but someone like Brian Nichols isn’t. It just shows I think the arbitrariness of the whole thing,” Arceneaux said.

Race Factor

Data also shows race plays a factor in who receives and who doesn’t receive the death penalty.

As of Jan. 1, 42.4% of the people on death row or facing capital resentencing were white, according to DPIC; and although Black people make up 13% of the U.S., they make up nearly the same percentage as whites (41%) of the death row population. Latinos make up 13.75% of those on death row.

According to DPIC, the data shows that a suspect is more likely to be capitally charged if the victim is white, and the suspect is more likely to be convicted and sentenced to death.

“Since Furman and even before, the death penalty in the United States has always been disproportionately imposed in cases involving white victims,” Dunham said. “African Americans are murdered with the same frequency as white victims but three quarters of everyone who was executed in the modern era has been executed for killing a white victim.”

For example, in Alabama, 80% of the executions have been for murders involving white victims — and only 20% of the murders in the state involved white victims.

“The statistics are pretty overwhelming in terms of who is on death row in Alabama” said Randy Susskind, deputy director of Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative. “The race of the victim is a big factor. Homicide victims generally are about 50% white and a 50% African American, but over 80% of the people on death row are there for killing a white person.”

Alabama has the highest per death sentencing rate in the country, he added; Alabama has the fourth largest number of inmates (170) awaiting execution of the more than 2,400 people currently on death row. California, Florida and Texas rank ahead of Alabama with 692, 330 and 199 death row inmates, respectively, according to DPIC.

Years following the 1972 Furman decision, there have challenges to the death penalty when prosecutors sought capital punishment in cases of rape — resulting in the Courts ruling that death penalty must only be reserved for murder.

Historically, however, when the death penalty was imposed for rape, it was imposed almost exclusively in the states of the former Confederacy, Dunham said. All Southern states, with the exception of Virginia, currently allow the death penalty as a form of punishment.

“It was imposed overwhelmingly against African Americans and it was never imposed on any white person for the rape of a Black woman or girl,” Dunham said. “I think that the use of the death penalty for rape is probably the clearest example of the racist application of the law.”

States Differ on Capital Punishment

Since the Furman decision, more than 1,500 people have been executed and more than 9,700 death sentences have been imposed throughout the country. Half of states in the Midwest and almost all states in the West have the death penalty.

States in the Northeastern U.S. have moved away from the death penalty, though Pennsylvania has had a governor-imposed moratorium on capital punishment since 2015. Moratoriums are also in place in California and Oregon.

The death penalty is typically reserved for more heinous crimes such as capital murder, but capital murder standards differ in each state. The nature of the crime is often imposed arbitrarily as well.

For example a serial killer responsible for the murder of at least 48 women in Washington was offered a path to escape the death penalty by cooperating with authorities in locating the bodies of some of the victims. The “Golden State Killer,” responsible for at least 13 murders and rape, was sentenced to life in prison.

“People who didn’t kill anybody, but were getaway drivers in robberies gone bad have been executed, even people who did not intend for the murder to take place,” Dunham said. “Everywhere in which the death penalty exists there are significant inconsistencies between who gets the death penalty and who doesn’t. and there are examples of people who committed objectively more horrible murders, receiving life sentences with people who committed or were less responsible for murders being sentenced to death.”

DPIC plans to release a report this year that shows that about half of all the death row sentences come from only 2% of the counties in the U.S., and that currently 1.2% of all the counties in the U.S. account for half of everyone on death row.

“The data shows that the death penalty has been administered in a way that is racially disproportionate, geographically arbitrary and arbitrary based on just the time and the social conditions,” he said, adding that attitudes and political inclinations of local (district) attorneys influence the use of death penalty.

Since 2009, more than one-third of Alabama death sentences were imposed in Etowah, Houston and Mobile counties, which contain only 13% of the state’s population, according to EJI data.

“Some counties are very active and other counties are not. Sometimes they’re rural. Sometimes they’re urban, but the arbitrariness is that it really does depend on where you live, whether the death penalty is something that’s on the table for people who commit murder,” Susskind said.

DPIC data shows that form the time executions resumed in 1977 following Furman through April 2020, 82% of all executions in the U.S. have taken place in the South. From January 2015 through April 2020, just 5 states — Texas, Georgia, Alabama, Florida and Missouri — carried out 83% of all U.S. executions, DPIC data shows.