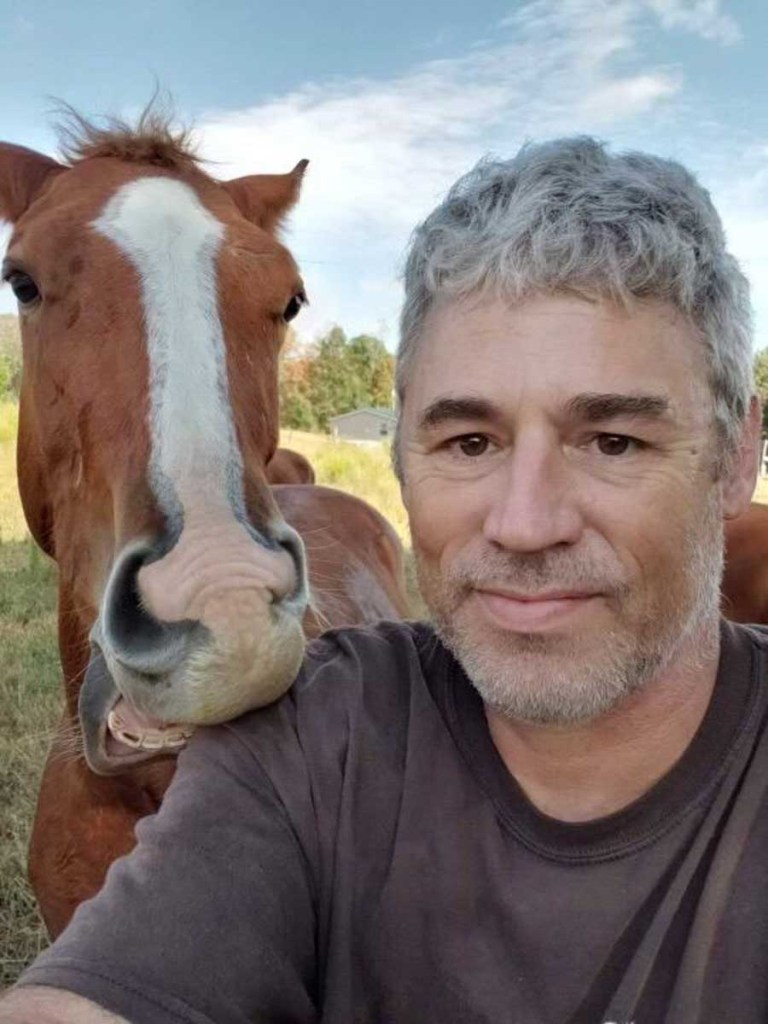

(Community heroes) A medic’s training: Army veteran Michael Elston on how desert conflict shaped his Nursing career

Published 2:30 am Friday, November 11, 2022

- Now a registered nurse at UAB’s Neurosciences Intensive Care Unit (NICU), Michael Elston continues to expand on the medic’s skills he learned over the course of five combat deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Whether your living memory encompasses the second World War or more recent engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, one thing remains the same for veterans who return home after fighting America’s battles overseas.

“When you get out of the military, you kind of miss the tight-knit camaraderie you had,” says Cullman County veteran Michael Elston, now retired from a lengthy career as a medic in the Army.

Trending

“More than likely, everybody who was in the military felt that camaraderie while they were in and the VFW, the American Legion, the Disabled American Veterans — they’re all fraternal organizations that try to give that camaraderie back. It’s something vets often miss and they don’t even realize it.”

Now a registered nurse at UAB’s Neurosciences Intensive Care Unit (NICU), Elston continues to expand on the medic skills he learned during the course of five combat deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan, including tours though both Operation Desert Storm (in the early 1990s, not long after graduating from high school) and during the mid-2000s in Operation Desert Shield.

Though his UAB job schedule has made Elston’s local visits with fellow veterans at Cullman’s VFW Post 2214 less frequent of late, he’s a strong believer in the value the VFW offers as a place where vets can connect with others who’ve experienced military life from the inside — something that’s tough to duplicate with relationships forged in the civilian world.

“They’re not just sitting around drinking at the bar, smoking and telling war stories,” he says. “It’s a way that you can be with people who have experience with similar things and once again feel that closeness. And, are a good group of guys. They’re very focused on helping out vocal vets.”

Raised in a military family who traveled for work, Elston enlisted in the Army before graduating high school in 1987 in Ocala, Fla. After an extended military career that progressively stepped up his administrative roles with successive deployments, he and his family decided to settle close to his parents (his father, Gerald Sandlin, is also an Army veteran) in Cullman County.

An Army medic’s training follows a different path from the conventional academic one that civilians take in school to purse a nursing or other health care career. “Basically, both your Navy corpsmen and your Army medic, are given a little over two or three months of medical training after Basic training — and then they’re thrown to the wolves,” says Elston.

Trending

“As an older service member, I can look back and say I knew enough, coming out of my medic program to be an incredibly dangerous individual. They do teach you the basics, but you don’t really learn to be a good medic until you get to your unit, and your sergeants and PAs and doctors sit you down and teach you things you really need to know, and that goes on through the rest of your career: You’re always learning.”

Modern U.S. deployments tend to organize around operating bases that protect much of a conflict’s support infrastructure at a defensible distance from enemy lines. But medics still must know how to function in a combat environment, says Elston, because there’s no illusion of safety — even from behind the wire.

“The lines aren’t clearly drawn. If you think about World War II; even World War I, they were on the trench lines for months and months at a time — they were just ‘there.’ Even though in World War II they were on the move, they were in that continuous combat situation for a very long period of time. Whereas in Iraq and Afghanistan, you’re having skirmishes where the combat is hours long — not days; weeks; months. Then you’re back into a secure area. I mean, it’s major kudos to those soldiers back in World War II. I know I would not have wanted to have been in that situation.”

Still, present-day geopolitical positioning and the ever-emergent technology of warfare mean that veterans of more recent U.S. conflicts bring home their own distinct experiences. “The majority of the individuals who get deployed overseas don’t actually go into a combat situation,” says Elston. “They may be in an area that is a combat zone, but they stay in a secure contained area and don’t go, as we’ll call it, ‘outside the wire.’ There are missions like that, where you going in and kicking doors, and then there are support missions … Those are not necessarily ‘combat’ missions, but they’re support missions in a combat area.

“Even those who are in logistical support and combat support of the logistics roles will have ‘seen’ combat,” he adds. “But it’s a different role. I was always assigned to combat arms: We went on the missions where we’re kicking in doors. A couple of my later missions, I was in an instructor’s role, where I’m training indigenous personnel to operate [as medics] in a combat role … As a medic, I’ve never been in a combat situation when I did not have at least one firearm assigned to me at all times. We’re soldiers before we’re medics. We’re having to make sure we’re establishing superior firepower before I can take care of my injured.“

Back on the civilian side of his Army life, Elston says he’s appreciative for the unique perspective his overseas training and experience have lent his career, both during later deployments with the Army, and in his present-day nursing role.

“A lot of people really have forgotten about Desert Storm,” he says. “That particular conflict was a huge learning environment, because even after the ceasefire came, it didn’t mean that there weren’t shots being fired. The Kurds were still fighting the Iraqis, and guess who the Kurds brought their wounded to?

“As a young medic, dealing with the traumas on those Kurds — it’s sad it happened to anybody, but it was a great learning tool for any of the young medics who got to take part. Because we learned a lot about the human body and how to treat it, and it was something that helped guide me along later, during peacetime, in teaching younger medics how to take care of the wounded on the battlefield.”