Braving the depths: Smith Lake divers face unique underwater challenges

Published 5:30 am Saturday, July 25, 2020

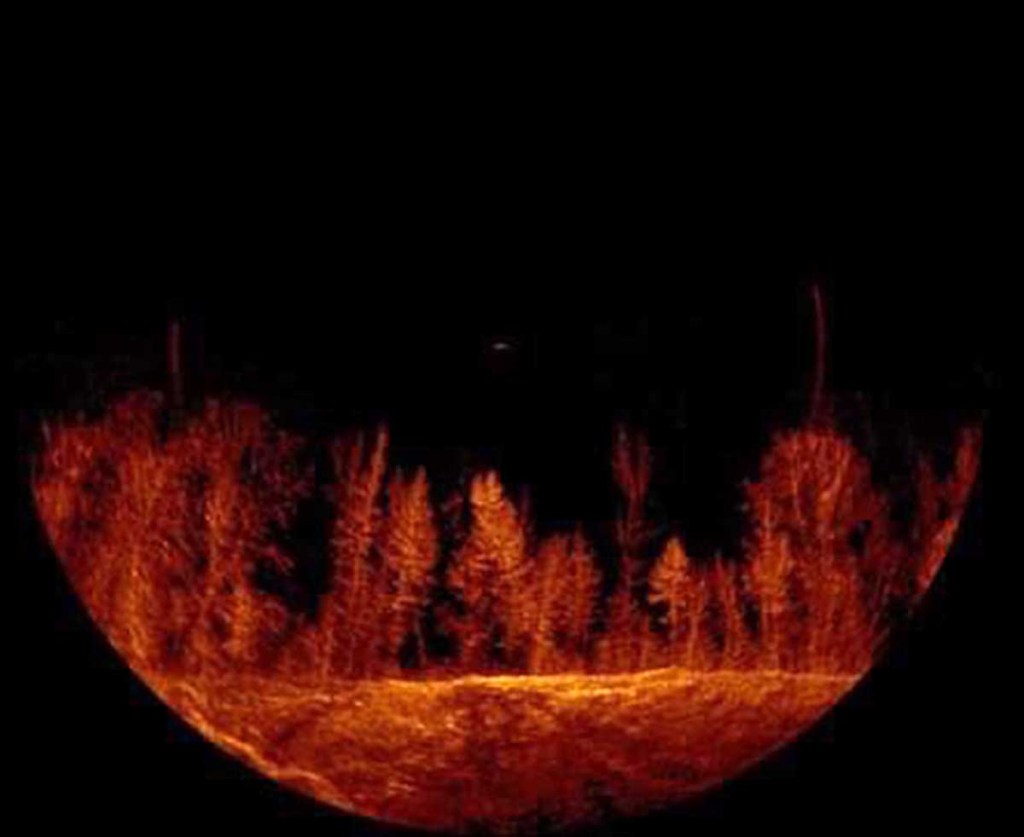

- Underwater cameras show the terrain of Smith Lake. Some of the trees are 50 and 60 feet tall, and the water is at depths of 165 feet and even 238 feet in areas.

As the recovery effort for a missing Smith Lake boater stretches into its second week, divers at the site of the man’s last known location on the water face a unique set of challenges that few — even seasoned enthusiasts who dive recreationally — will ever encounter.

Smith Lake is well known among longtime locals for its varied and murky underwater features, many of which still remain ever since the area was flooded intact when the reservoir was first created in 1961. Even when the weather above the surface is clear and warm, it’s a foreboding place for divers.

“We don’t recommend that standard recreational divers to go into Smith Lake, and the reason why is because of the hazards,” explained Eric Parker, a member and trainer of the Cullman County Sheriff’s Office’s Dive Team. “You have entanglement issues, from 60 years of fishing line, to standing trees, to houses that are still at the bottom. It’s a very broad hazard; really a lot of hazards. We have a lot of people who come from out of state who want to dive Smith Lake, and we take them to what we would say is ‘easy diving’ — and they still don’t like it, just because it’s always cold, dark, and bad visibility.”

In the area where divers are searching for 26 year-old Fultondale resident Dustin New, whose boat was found capsized July 16, Parker says there are particular challenges that make the search a delicate endeavor.

“About 60 feet off the bank, there’s an area where a part of the bank was clear cut, and the cutters just laid the timbers down as if you were in a forest and on land,” he explained.

“They only got so far with doing that, and then they just left the standing timbers there. So at about 60 feet, you start running into tree tops that are 75; 100 feet tall. Some of them still have pine needles and pine cones — they’re basically just petrified down there in the dark. The hazards of diving in that are extreme. The area where they’re searching is anywhere from 65 to 130 feet deep.”

Parker, a reserve deputy who also owns the North Alabama Dive Center, says Smith Lake is generally a tough outing for even veteran divers, with a variety of underwater conditions that make it hard to characterize the overall diving experience, all but assuring that each dive will be its own unique event.

“If you get something like a rock ledge or a rock bottom, the visibility might be as far as the beam of your flashlight. But up around Smith Lake Park, where it’s muddy and not very deep, the visibility is horrible. It really depends on what area you’re going to.

“We’ve had divers to actually swim into a house, and not even know that they were in a house — until they’ve had a very bad experience, which is when we have to go in and pull them out. You have to keep your head on a swivel and be aware of your surroundings. Really, you just have to imagine: if you look at old pictures of the area before they backed it up, all those land features; the trees and the houses — it’s all still there.”

Once you go beneath the lake’s thermocline — the technical name for the invisible subsurface boundary where temperature steeply drops off as the depth increases — houses and phantom trees aren’t the only dangers.

“When you get below that line, which is around 30 or maybe 40 feet, the temperature drops from the mid-60s to the high 50s almost immediately,” Parker said. “Your air consumption is going to go up because you’re cold, plus you’re in the dark — and you’re also fighting hypothermia. We do a lot of diving at Big Bridge because it’s kind of a controlled situation, and when we went out recently, down at around 116 feet the temperature was about 47 degrees. That stay pretty constant, no matter what the surface temperature is.”

Alabama Power created the lake nearly 60 years ago, flooding the watershed beneath the Lewis Smith Dam on the Sipsey Fork of the Black Warrior River. While the hydroelectric project eventually would transform the shoreline and the lake itself into a highly prized recreational area, the fun stops at the water’s surface. Even after years of diving, it takes more than an impulse to spur intrepid divers into the water — especially those who know the lake’s dangers.

“You have to really love, or really want, to do it,” said Parker. “It’s like fire fighters running into a burning building. There has to be a reason. Diving for these recoveries is some of the most dangerous stuff you can do in all of diving.”