Lynching cold cases on Georgia lawmakers’ radar

Published 6:00 pm Thursday, March 17, 2022

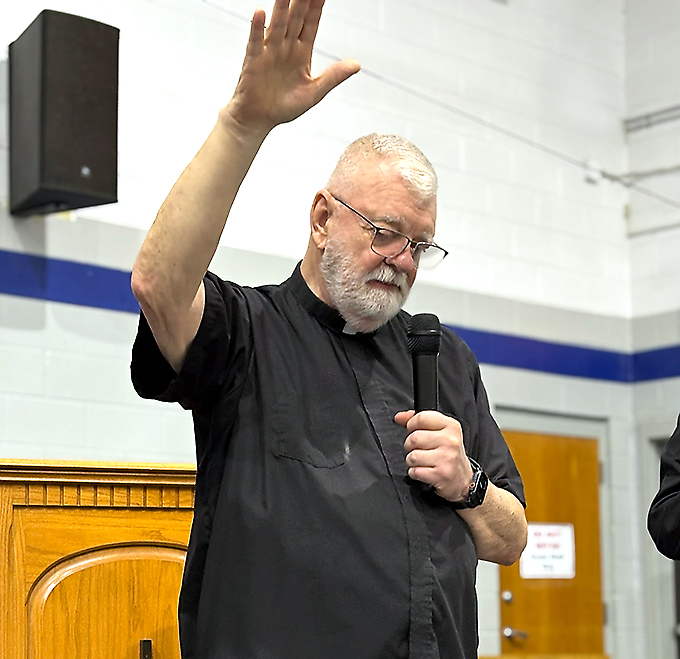

- Lee Henderson, standing by the Mary Turner memorial marker, recounts the story of the lynching that claimed her life and many others.

ATLANTA— Following the enactment of new hate crimes and citizen arrest laws in Georgia, lawmakers say now is the time to bring justice to cold case lynchings that happened in the state.

Georgia Rep. Carl Gilliard dropped a bill March 11 that aims to create the Georgia Cold Case Project to Address Historic Lynchings. Under the proposal, the DCA Department of Community Affairs with the GBI, would lead the project, investigating and, if possible, redressing, any unresolved historical homicides or lynchings.

“What it does for those (murders) that have passed a statute of limitation is a ‘Say your name piece.’ For them to divide all of those names and tell their stories” Gilliard said. “The other part is a part that the statute of limitations has not passed. When you look at those people who know something that are still living from the Civil Rights Movement to now. And just like a regular murder case, we’re just not saying anything about it.”

A lynching is typically defined as a unlawful killing, usually carried out by a mob.

While the Georgia proposal seeks to have all unsolved lynchings investigated through the proposed project, some of Georgia’s most notable mass lynchings are the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 and the Camilla Massacre of 1868 — which was sparked by the expulsion of Georgia’s “Original 33” Black members of the Georgia General Assembly in 1868 due to their race. A bill authorizing a monument in honor of the “Original 33” was approved by state senators March 15 and now awaits a House vote.

“These are cold cases, civil rights era and all the above,” said Gilliard, also referencing the 1915 lynching of Jewish American Leo Frank in Marietta. “That’s why when you talk about even a day like today with Asians and people of color now still being [victims], it’s not a Black bill or white bill.”

More than 500 cold cases would fall under the purview of the proposal, Gilliard said. His brother’s 1957 lynching is one of them.

“Long before I was born, they lynched and mutilated him and cut him into pieces,” he said. “Georgia has a past and we’ve got to do something to give these people what they deserve. We may not get every last case out of the 500 some odd cases that we know of, but if we get one more than we’ve had, we’re moving in the right direction.”

The proposal also seeks to pardon and exonerate unresolved lynching cases for the victims who were wrongly or unjustly accused or convicted of a crime, or lynched where there was not sufficient evidence to prosecute or convict them.

Many organizations have researched lynchings in the South and Georgia, many of the lynchings attributed to being racially motivated.

Gilliard said he anticipates many organizations that have researched lynchings to continue to do so through next year’s legislative session. The bill encourages the GBI to partner with such organizations like Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the State Bar of Georgia, Emory University’s Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project and ACLU.

“There was nothing natural or inevitable about racial segregation. It was established, maintained, and enforced through terror and violence against formerly enslaved people, their children and grandchildren,” said ACLU of Georgia Executive Director Andrea Young. “These families and communities deserve to know the truth.”

The Georgia proposal was read in the Georgia House of Representatives on March 15, but won’t move forward this session following the state’s March 16 “crossover day” deadline to approve bills in the chamber.

It comes as Congress approved the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act that would make lynching a federal hate crime in the U.S. The bill is named in honor of a Black teen in Mississippi who was reportedly lynched after offending a white woman in 1955.

Georgia ranks second in the highest amount of reported lynchings, 593 between 1877-1950, according to EJI.

Four lynchings are documented in Lowndes County: Will Lowe in 1890, David Goosby I 1894, Caesar Sheffield in 1915, (unknown) Lewis in 1916.

The EJI reports that Sheffield, a husband and father in his 40s, was jailed for allegedly stealing meat from a store owned by a white man. A mob of white men took him from the jail and shot him to death.

In recent years, the Lowndes community has come together to recognize the 1918 lynching of the pregnant Mary Turner, who was among more than a dozen killed in Brooks County after a series of South Georgia lynchings near the Lowndes-Brooks County line following the murder of her plantation owner.

Her death has become one of the most talked about in recent years as it demonstrates the brutality not only against Black men, but also women and children.

“They lynched her upside down and built a small fire under her head and basically smoked her so to speak,” said Lee Henderson, who spent years researching Turner’s death at Valdosta State University, in a previous interview. “(A man) cut her open, the baby falls down on the ground, the baby began to scream.”

A historical marker dedicated to Mary Turner and the people killed in the Brooks-Lowndes County lynchings was installed at the site of her death.

Two lynchings were documented in Baldwin County, eight in Thomas County, and in Tift County, the lynchings of Ed Henderson in 1899, two unknown people on Jan. 29, 1900, and Charles Lokie in 1908.

An Aug. 10, 1908, newspaper report states Lokie was lynched for “making insulting remarks to a prominent white woman.” Later, several people were out viewing the corpse during the day.

An Oct. 17, 1935, edition of The Moultrie Observer reports that Bo Brinson was shot to death after trying to prevent a group from searching his house for a wanted murderer. He was one of seven reported lynchings in Colquitt County.

Five men were lynched in Whitfield County, including A.L. McCamy in 1936 who was killed in Dalton for allegedly attempting to attack a white woman. According to reports, a white mob overtook the Whitfield County Jail to get to McCamy and later hung him from a tree.