For local cattlemen, all woes lead to water

Published 5:15 am Sunday, January 15, 2017

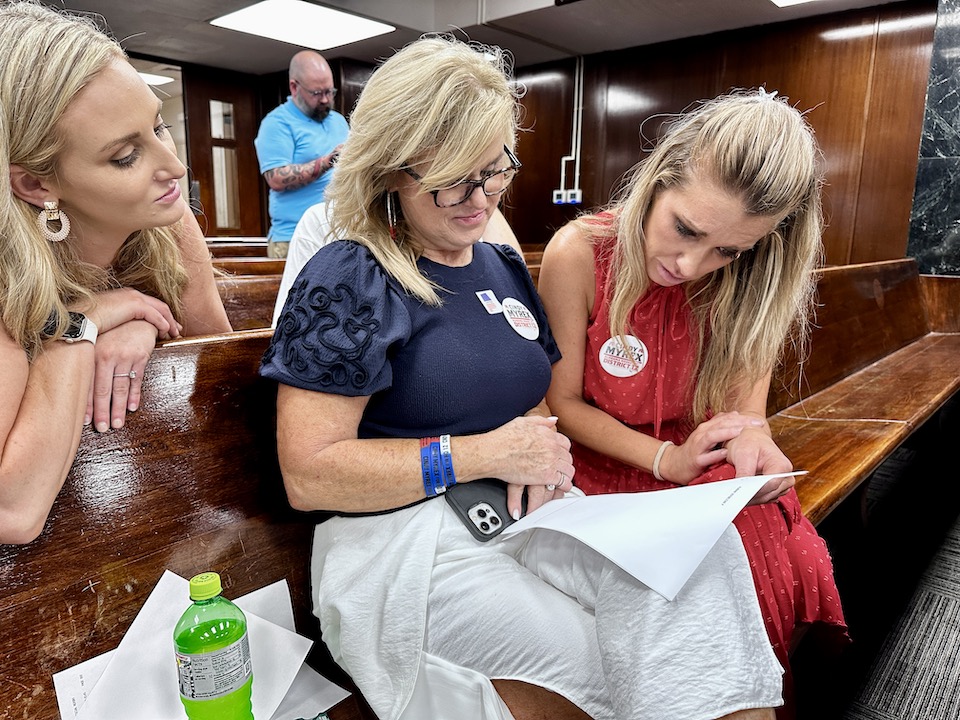

- Steve Lake stands by as cattle graze on some hay at his farm in the Battleground community Friday, Jan. 13, 2017.

The effect of a persistent drought on local people who earn an income from the sale of cattle is hard to quantify or capture in an easy, snapshot sort of way.

Trending

There are a lot of variables in the cattle market, at the local, regional, national and international level. There are market forces, currency shifts, weather whims, fickle consumers — even pests and pestilence.

Sometimes, several of those things hit a cattle-producing area all at once. And, from the start of the 2016 spring growing season until now, that’s exactly what’s happened in Cullman County.

It starts, of course, with the drought.

“We may not be in the worst drought situation there ever could be — like in the desert,” said Dr. Terry Slaten, a hobby cattle farmer who’s perennially active in the Cullman County Cattlemen’s Association. “But we’re close.”

Drought has primarily affected the amount and quality of the hay grasses that local cattle forage in the warmers months and eat from baled stock in the winter. It’s prevented local grass from reaching its full nutritional value as it grows, and it’s slowed the growth so dramatically that farmers aren’t able to cut and bale their hay as often.

That scarcity, in turn, has only served to drive up the price of hay — whenever it’s been available at all.

Trending

“I remember in June last year: there was nothing out there in my pasture,” said Slaten. “I’d just bought hay from a gentleman who had some for sale. I started feeding hay in the middle of summer — which is really odd; really early. I prayed for rain. And it did rain, in early June right after we put our fertilizer out. And then it did not rain again for all the rest of June on our farm.

“What happened with me — it happened with all the other farmers in Cullman County. We got some rain; the grass started growing and it looked like things we going to be okay — and then nothing. People got their second cutting of hay, in mid-to-late July, and that was just about it.

“If anybody around here tells you that they got a fourth cutting last year…well, they’re probably lying.”

Most local farmers know about the hay cutting cycle. In a typical year, a hay field can yield at least three regular hay harvests, or cuttings, throughout the spring and summer months, as well as a fourth cutting in early fall that, in good times, retains adequate protein and nutritional value to be useful as forage.

But in Cullman County, the 2016 hay season was marked by low-quality grass and a severely delayed cutting schedule — almost from the start.

“Folks are scratching to get hay,” said Steve Lake, a Battleground cattle and poultry farmer who runs a herd of about 100 head. “But folks also are really struggling with is that most of our cattle farmers will sow for grazing, typically in September or October.

“Well, nobody got theirs sown this past year until December, because of the drought. The rye grass that people use for winter grazing is behind, and we’re not getting the help from it that we’re used to, because it was so late getting in the ground.”

This is how a drought can become such a systemic problem for the cattle industry. One major problem — a lack of rainfall — launches and exacerbates new ones that follow their separate, forking paths, until they converge later to make matters worse.

“When the rain cut off last year, people were not able to get the hay that they needed,” said Slaten. “And that absolutely affects the price of hay. If you do find it, it’s somewhat expensive.

“Like any commodity, cattle is very much a supply-and-demand market. And two summers ago, cattle prices were the highest they had ever been; just unbelievably high. Everybody thought we were about to be in really good shape…and then this kind of perfect storm happened. The dollar got stronger. It costs farm countries more to buy stuff when that happens.”

Then a drought in Texas — a massive market for cattle — forced a lot of farmers out of business. The Texas market revived, and overcorrected, when a post-drought glut of calves came of age. The oversupply drove cattle prices down further. Beef had become cheap again.

The price of beef everywhere affects the value of cattle anywhere, including Cullman County. With the price of beef already at new lows, along came another problem.

“Armyworms. They’re called Fall Armyworms,” said Slaten. “They started hitting people here in late July, and it went through August and September. It can turn a green hay field to brown. It was just one more thing that we had to deal with.”

At the end of the day, it all comes down to water. Lake, who’s always run his livestock on ponds, was forced to convert to utility water last summer as his ponds shriveled.

“This was a big drought; not just a typical dry spell,” he said. “I’ve never in my lifetime seen it this way. “A lot of people remember 2007. And 2007 was dry year; a tough year for cattlemen — but we didn’t see ponds go dry. My ponds were drying up this year. A lot of people’s ponds have not filled up yet. Fortunately, mine have; they’re supplied by a big watershed.

“But I went to city water back in the summer, and in the fall is when I put my cattle on it. I’d never had my cattle on city water before. Numerous, numerous people in the cattle business had to go to city water this year.”

As a hobby farmer, Slaten isn’t dependent on livestock as his primary source of income. Even in the most difficult of times, he’s able to see the upside of being in the cattle business.

“I think, going down the road, agriculture is going to be an excellent place to be,” he mused.

“There are a lot of things we do in life that are optional — but eating is not one of them.”

Benjamin Bullard can be reached by phone at 256-734-2131 ext. 145.