White, rural drug users lack needle exchange programs to prevent HIV infections

Published 12:00 pm Wednesday, November 30, 2016

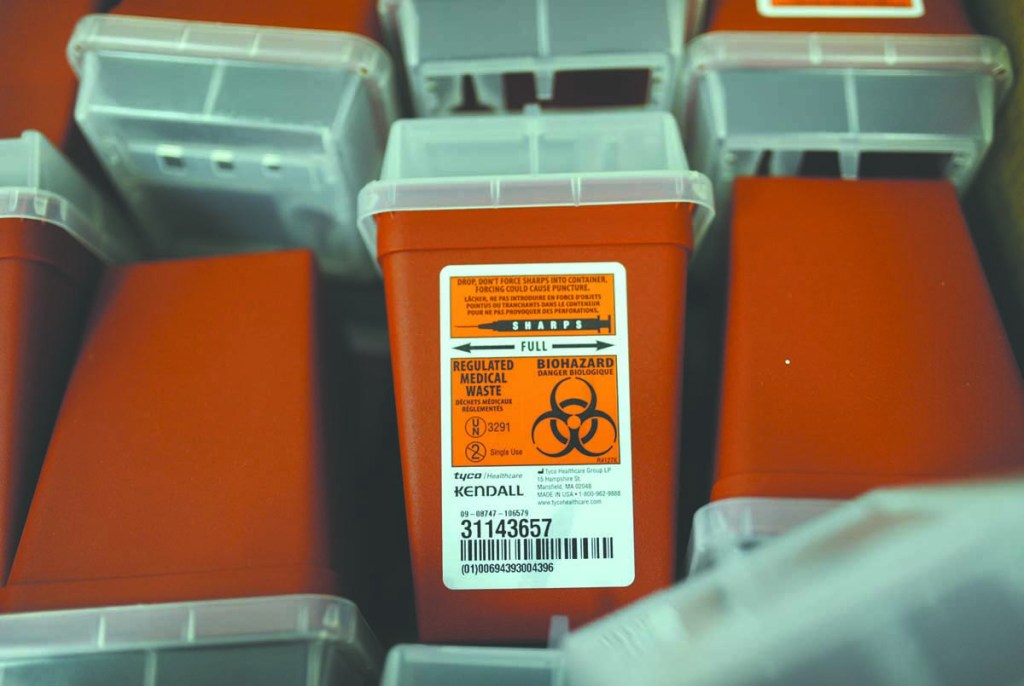

- Medical waste containers are stored in preparation for Scott County residents that are looking to exchange used needles at the Community Outreach Center in Austin as part of the needle-exchange program authorized by Gov. Pence. "The goal is a clean syringe for each injection use," said Brittany Combs, Scott County Public Health Nurse.

Needle-sharing by opiate addicts is fueling an alarming rise in new HIV infections among injection drug users, and the United States doesn’t have enough syringe programs in place to reduce that risk, according to a report released Tuesday.

Although needle exchange programs have been politically controversial for decades, studies have demonstrated their public health benefits in dramatically reducing the rate of HIV transmission and risk of hepatitis infections among injection drug users without increasing the rate of illegal drug use.

The new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that use of these programs has increased substantially during the past decade, but most people who inject drugs still don’t always use sterile needles. Sharing needles and syringes is a direct route of transmission for HIV and hepatitis B and C viruses.

As a result, decades of progress in reducing HIV spread by dirty needles is being threatened. People who would not have been considered at risks for these infections are now vulnerable, especially white people living in predominantly rural areas of the country, including Appalachia, rural parts of New England, and the Ozarks.

“The big picture here is that we’ve had a lot of progress reducing HIV infections spread by needles and we’re at risk of stalling or reversing that progress,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden in an interview. As a result of the opioid epidemic, he said, “more people appear to be injecting drugs, more people are sharing needles, and there are more places not covered by syringe service programs.”

For the first time, in 2014, whites who inject drugs had more HIV diagnoses than any other racial or ethnic population in the country, the report said.

Needle exchanges not only provide sterile needles and syringes, they can also help people get counseling, disease testing for HIV and hepatitis C, and referrals to places where patients can get treatment. The services are particularly important because people addicted to drugs often may not seek or get medical care.

Officials said a 2015 HIV outbreak in Indiana, while Vice President-elect Mike Pence was governor, was a wake-up call that public health’s worst fears could be realized. About 200 people in a county of 24,000 people were diagnosed with HIV infections, making it the worst outbreak in state history, fueled by opioid addiction and needle sharing. Scott County, the epicenter of the outbreak, ranked last out of the state’s 92 counties for poverty, unemployment, and percentage of people who were uninsured.

At the time, syringe exchanges were illegal in the state, and Pence was against them.

After federal officials warned of the growing epidemic, Pence signed emergency legislation allowing syringe exchanges in the county. He eventually signed statewide legislation that allows needle exchanges, but only if counties ask for permission in light of a public health emergency.

Indiana’s outbreak was a “sentinel event,” an indicator of what could happen in more than 200 other communities in 26 states that are at risk for similar outbreaks, Frieden said.

Although decisions for syringe service programs are made at state and local levels, there has been intermittent federal funding in recent years. Asked whether the incoming Trump-Pence administration could put that federal funding in jeopardy, Frieden said: “When people look at the data and are faced with the real challenges, they see that these are programs that save lives and save money.”

CDC researchers have identified 220 counties most vulnerable to an outbreak of HIV or hepatitis C by analyzing factors including overdose deaths, pharmacy sales of prescription painkillers and unemployment and poverty rates. At an infectious disease conference in New Orleans in October, CDC researchers presented a U.S. map showing those vulnerable counties and the locations of syringe service programs.

“There’s a striking mismatch,” said John Brooks, a senior medical adviser at CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. The vulnerability assessment “demonstrates what parts of the county we’re very concerned could have an event like Scott County,” he said. In states like Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia, more than 40 percent of each state’s counties are considered vulnerable to rapid spread of HIV and new or continuing high numbers of hepatitis C infections among injection drug users.

The North American Syringe Exchange Network estimates there were 228 syringe service programs in 35 states, Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and Native American lands. Only 17 states and Washington, D.C. authorize needle-exchange programs.

Congress first prohibited the use of federal funds for syringe service programs in 1998, when Sen. Jesse Helms, R.-N.C., persuaded Congress to issue the ban. Before becoming governor of Indiana in 2013, Pence supported the ban during his six terms in Congress.

Congress lifted the ban in 2009 and reinstated it in 2011. In December 2015, following the HIV outbreak in Indiana and rapidly rising rates of injection drug use across the country, Congress modified the restriction. Federal funds are still prohibited from paying for sterile syringes, but funds can be used for other parts of the program if there is an HIV outbreak or risk for a significant increase in hepatitis infections. CDC has approved requests from 15 states and select counties to use federal HIV funds for syringe programs.

The CDC report shows that among African American and Latino drug users, the syringe programs have helped reduce HIV diagnoses, but the decreases in HIV diagnoses among whites who use drugs is much smaller. That decrease also stalls after 2012, and officials attribute that to the steadily expanding opioid epidemic.