Health officials: Hepatitis C infections on the rise in Kentucky

Published 11:40 am Wednesday, May 4, 2016

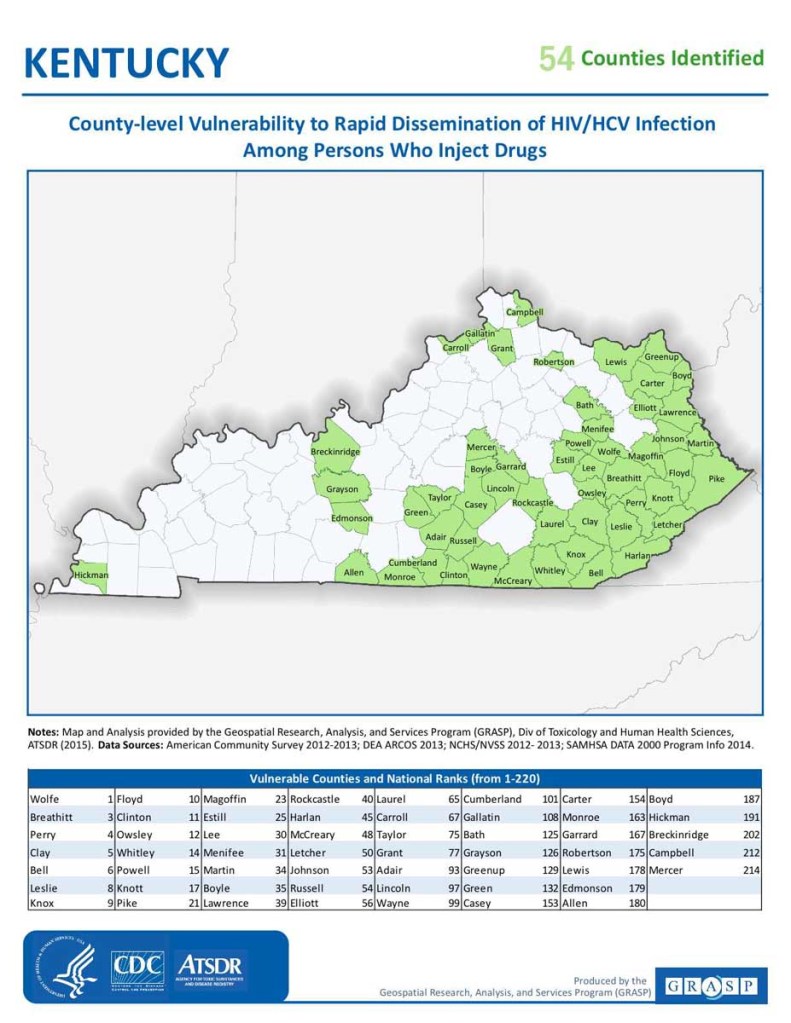

- Vulnerable counties in the state of Kentucky

Health officials in central Kentucky say the rate of the Hepatitis C infection is on the rise locally as well as nationally.

“The health department receives reports of hepatitis C infections almost daily,” Jim Thacker, public information officer for the Madison County, Kentucky Health Department (MCHD) said recently. “We are certainly dealing with an increase in that number, which before had remained quite steady. It’s indicative of a disturbing trend.”

A liver infection caused by the Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis C is short-term illness caused by a blood-borne virus. For a large number of those infected, Hepatitis C becomes chronic, which can result in long-term health problems and even death. Currently, there is no vaccine for the virus.

Health officials say the recent cases of HCV are directly attributable to intravenous (IV) drug use and needle sharing among drug users.

To make matters more grave, a recent CDC report showed new cases of HCV more than tripled in Kentucky and nearby Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia between 2006 and 2012.

But the bad news doesn’t end there.

Prompted by the recent HIV epidemic in Austin, Indiana, which forced the state’s governor to declare a public health emergency for Scott County and was attributed to the IV use of the painkiller Opana, CDC researchers conducted a study to rank counties across the nation which are especially vulnerable to the rapid spread of HIV or hepatitis C infection if the viruses were to be introduced into the population.

According to the report, the CDC based its rankings on unemployment, number of drug overdoses and opioid sales, among other factors.

Of the top 220 counties listed in the report, researchers identified 54 counties in Kentucky alone as being especially vulnerable to an outbreak.

More than half of those counties, which include Wolfe, Breathitt, Perry, Clay and Estill, are located in the Appalachian regions of Kentucky where access to health providers is especially poor and higher rates of poverty compound the issue.

“While Madison County did not make the list, we are surrounded by communities that have been identified as vulnerable. With the documented rise in the use of drugs such as heroin, we are at risk and have potential for a possible outbreak,” Thacker explained.

Nationally, reported instances of acute Hepatitis C have climbed steadily in recent years, growing from 781 in 2009 to 2,138 in 2013.

In Austin, Indiana, more than 180 people have been infected with HIV — many also infected with Hepatitis C. Local health officials say the warning signs for a similar outbreak in Kentucky are present.

Health officials say HIV and Hepatitis C testing is one way health departments can track and control infections.

“Thankfully all counties in Kentucky can test for HIV and recently Madison County became one of the counties that now offer Hepatitis C testing,” Thacker said. “We have had the service for the last month.”

Thacker said regular testing for people at risk is especially important, as approximately 70 to 80 percent of persons with acute Hepatitis C do not experience symptoms. HIV can be present in the body up to three months before a person shows signs of infection.

Needle exchange programs have been suggested as a possible strategy for combating HIV and HCV infections within the state as IV drug-use soars.

“We often hear about diabetics selling their extra insulin needles to desperate drug users,” a local substance abuse counselor, who wished to remain anonymous to protect patients, told The Richmond, Kentucky Register last week. “In addition to the dealers where they get their heroin or other drugs from, many users have a person they pay who offers them clean needles. One user told us while the heroin was cheap and easy to get, her needle contact would often charge double and sometimes triple what the drugs cost. Many addicts simply can’t afford clean needles so they take shortcuts or result to stealing what they need.”

Thacker said the MCHD have been looking into adopting a needle exchange program, but acknowledged that while the program might decrease the risk of infection, it does little to help the core problem of addiction.

“We are looking at one,” Thacker said. “There have been some public meetings and we have had discussions. However, it’s a tool in the toolbox and not the magic bullet that is going to stop the problem. It could possibly decrease the rate of infection, but the problem of drug use is still there.”

Barker writes for the Richmond, Kentucky Register.