Scientists found a nearby black hole burping out gas

Published 10:15 am Thursday, January 7, 2016

- Merging galaxies may have given this black hole a burp-worthy meal.

We at Speaking of Science love a good black hole burp. And scientists love them, too!

“For an analogy, astronomers often refer to black holes as ‘eating’ stars and gas. Apparently, black holes can also burp after their meal,” Eric Schlegel of the University of Texas said in a statement put out by NASA. Schlegel is the lead author of a new study on these cosmic belches, which was presented Tuesday at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

These blasts of matter that black holes expel, which scientists believe help regulate the size of the holes and create new stars nearby, can be hard to catch. In fact, it was only in late November that a research group claimed to have caught the entire process (the entire star meal, if you will) with belch included.

“Our observation is important because this behavior would likely happen very often in the early universe, altering the evolution of galaxies. It is common for big black holes to expel gas outward, but rare to have such a close, resolved view of these events,” Schlegel said.

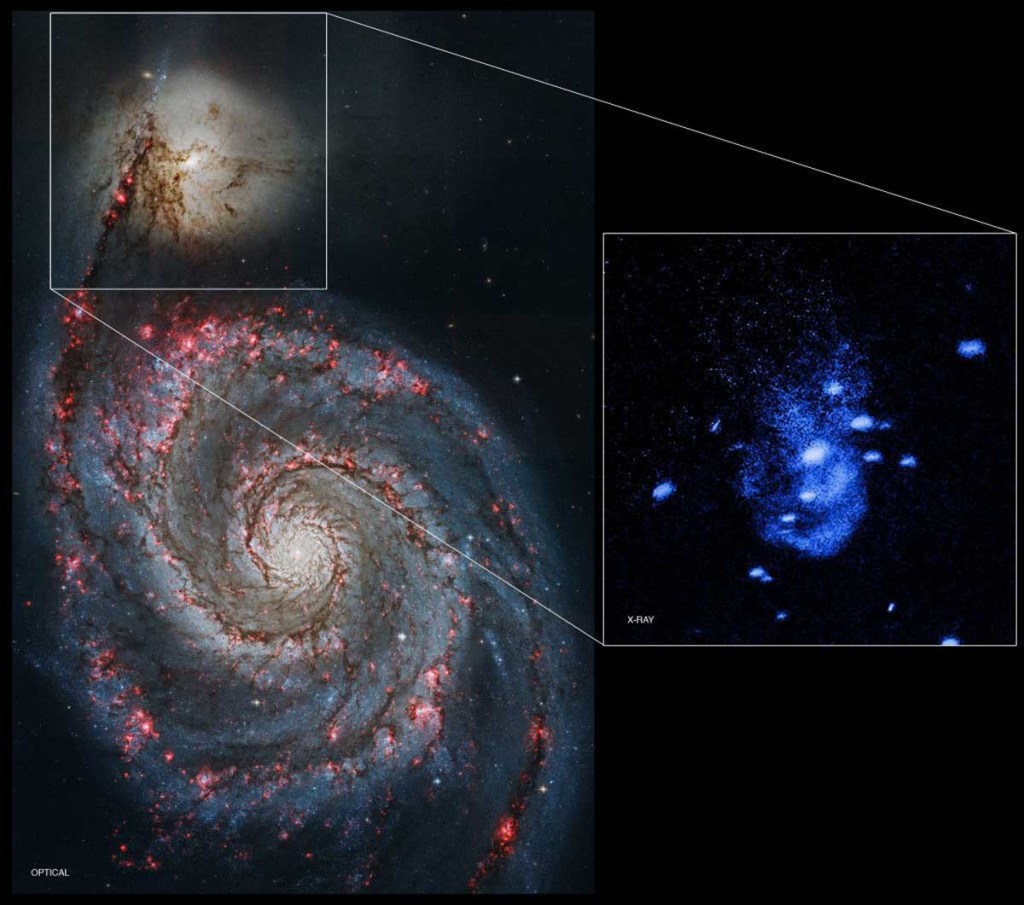

The black hole studied in November was a staggering 300 million light years away, but the super-massive black hole observed by Schlegel and his colleagues is in our cosmic back yard: It’s just 26 million light years away in the Messier 51 galaxy system. The black hole sits in the center of a small spiral galaxy that’s working on merging with a second, larger spiral galaxy. It’s likely that this cohabitation gave the black hole some gaseous material to chow down. Black holes aren’t very discerning eaters: They consume anything that comes past the point of no return known as the event horizon.

Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, the researchers spotted twin arcs of X-ray emissions from the black hole in question, which they believe to be the aftereffects of a big meal that happened millions of years ago (the jets, they say, would have taken 1 million to 6 million years to reach their current positions). They also noted a burst of colder hydrogen gas in the trajectory of the jets, suggesting that the hot burp had “snow plowed” other gasses into shape on its way out into the galaxy.

“This activity is likely to have had a big effect on the galactic landscape,” co-author Christine Jones of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics said in a statement.