Virginia teen admits running pro-Islamic State Twitter, helping man join terror group

Published 6:55 am Friday, June 12, 2015

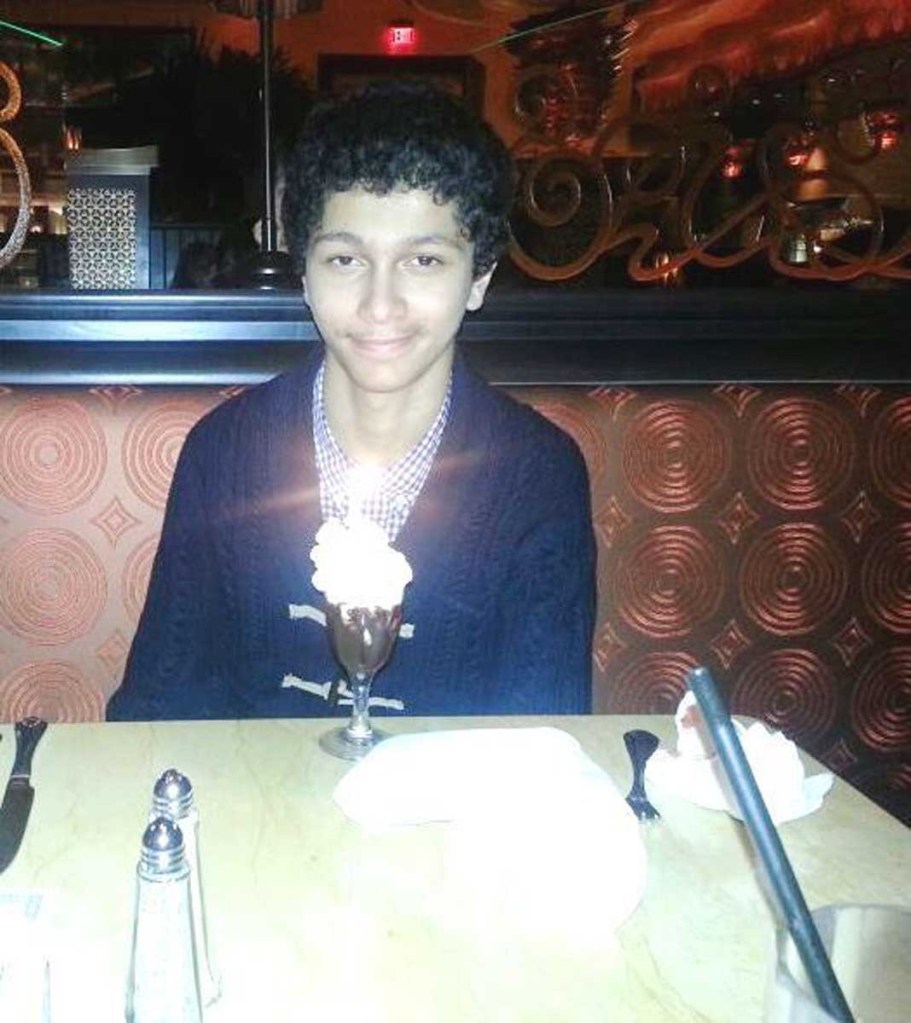

- Ali Shukri Amin

WASHINGTON — As federal authorities began to close in, the northern Virginia teenagers set off to Dulles International Airport in hopes of launching a dangerous mission: get one of them to Syria to fight with the Islamic State.

The January ride was the culmination of months of planning. Ali Shukri Amin — a suburban high school student who secretly ran a popular pro-Islamic State Twitter account — had forged connections with supporters of the terrorist group overseas, and now he was putting them to use. Reza Niknejad, his 18-year-old friend, was set to fly to Turkey, meet up with Amin’s contacts and, eventually, make his way into Syria.

On Thursday, Amin, 17, pleaded guilty in federal court as an adult to conspiring to provide material support to terrorists. His friend, according to court records, is now believed to be a member of the Islamic State in Syria. In a call to his mother not long after he left the United States, Niknejad said that he would “fight against these people who oppress the Muslims” and that he would see her in the afterlife, the FBI alleged.

Federal authorities said the case is a chilling reminder of the Islamic State’s pervasive online presence and ability to woo American youths. U.S. Attorney Dana Boente, whose prosecutors in the Eastern District of Virginia handled the case, said that the Islamic Sate’s social media use is “unprecedented” and that federal authorities were investing significant resources into bringing to justice those who use the Internet to provide real help to terrorists.

“They’re just kind of flooding the airwaves, so to speak,” he said.

So far, Boente said, federal prosecutors across the country have charged nearly 50 people with helping or trying to help the Islamic State.

Amin’s and Niknejad’s cases are, in ways, emblematic of the phenomenon, and, in other ways, unique. Both were born abroad — Amin, according to his attorney, in Sudan, and Niknejad, according to court records, in Iran — but both were naturalized citizens who came to the United States early in their youth. Both, for a time, were students at Prince William County’s Osbourn Park High School, though Amin withdrew in February and Niknejad graduated last June.

Both, federal authorities said, would eventually become radical supporters of the Islamic State.

“Make no mistake,” said Andrew McCabe, the assistant director in charge of the FBI’s Washington Field Office. “This case is a tragedy.”

The teens’ views were not always obvious. Those who knew Amin — who was arrested earlier this year — have said he seemed like a typical teenager. His attorney said he was once an honor student at Osbourn Park, did volunteer work and had been accepted to college before he withdrew.

But according to his plea, Amin also had a secret online identity: He was behind the controversial and prolific @AmreekiWitness Twitter handle, an unabashedly pro-Islamic State account whose manager drew news coverage for sparring with the State Department, postulating how digital currency might be used to fund the Islamic State and opining on the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri.

Amin tweeted more than 7,000 times from the account, broadcasting his controversial views to more than 4,000 followers, according to his plea.

Joseph Flood, Amin’s attorney, said in an interview and in a statement that Amin’s support for the Islamic State was largely born from his anger at the regime in Syria and his perception that the United States had tacitly supported it. Flood said Amin is a Muslim, and his actions “are a reflection of his deeply held religious beliefs, but also his immaturity, social isolation and frustration at the ineffectiveness of nonviolent means for opposing a criminal regime.”

“In every regard, the activity that resulted in his conviction was an anomaly and at odds with the hard-working values he learned in his family,” Flood said. “Mr. Amin’s greatest hope is that others might learn from his errors and find pro-social, nonviolent ways of working for change.”

Amin, wearing a blue-gray jail jump suit and sporting a slight mustache, said little more than “yes, sir” during a roughly 10-minute court appearance. His mother declined to comment afterward. He is scheduled to be sentenced Aug. 28.

Less could immediately be learned about Niknejad, and efforts to reach his family were unsuccessful. He seemed to live in Woodbridge, and a Prince William schools spokesman confirmed that he was a 2014 Osbourn Park graduate. A neighbor said he was a respectful young man who once chastised a friend for cursing and seemed to enjoy gardening. A student by that name was quoted in an article in the school’s paper in 2012 about how Muslims are sometimes unfairly labeled as violent extremists.

“Some misconceptions are that we all are terrorists which is not true. The Book [Quran] underlines that killing one another is haram [sin], that includes bombing others as well,” Reza Niknejad said in the article.

Niknejad is charged with conspiring to kill or injure people abroad and conspiring to provide material support to terrorists and the Islamic State.

According to court papers, Amin “began an effort” to convert Niknejad to radical Islam, and he talked with Niknejad and several unnamed people from abroad about “traveling to Syria for violent jihad.” The group sometimes used code phrases such as “Syracuse” to represent Syria, “basketball” to represent jihad and “basketball team” to represent a jihadist organization, court papers allege.

McCabe said FBI agents were first tipped in November to Amin’s support for the Islamic State. By that time, the teen already had made a name for himself under the AmreekiWitness handle.

Rita Katz of the SITE Intelligence Group wrote in a Time column that the AmreekiWitness account once had a back-and-forth with the State Department’s anti-radicalization account. The Daily Mail wrote about the teen in August 2014, when his AmreekiWitness account opined about the unrest and police actions in Ferguson.

Amin also ran an ask.fm page, according to his plea, which he said was “dedicated to raising awareness about the upcoming conquest of the Americas, and the benefits it has upon the American people.”

Court records show that the FBI had won the right to search Amin’s phone as early as November, and it seized a package from him on Jan. 7 containing a smartphone with international capability, thumb drive and handwritten letter in English and Arabic. That, apparently, did not allow them to thwart Niknejad’s trip.

Though Amin expressed a desire online to travel, his role ultimately seemed to be that of a facilitator. His planning came to fruition Jan. 14, when Niknejad told his family that he was going camping. He instead left for Dulles with Amin and another person in what would turn out to be his first stop on a trip to Syria, authorities alleged.

According to an FBI affidavit, Niknejad — whose ticket was supposed to take him to Greece — met up with Amin’s contacts during a layover Istanbul, Turkey, and the group made its way to Syria. One of Amin’s contacts, according to the affidavit, stayed in touch with him during the trip, even sending pictures from the countryside as the group traveled by bus to the Syrian border.

Officials have said the person who drove with Amin and Niknejad to the airport was another 17-year-old student at Osbourn Park High. It was not clear precisely what that teen knew about the plans of the other two, although Amin told Niknejad during the ride where to go once he arrived in Turkey.

According to an FBI affidavit, Niknejad’s sister checked his bank records when he had not returned by Jan. 18 and found that he had purchased a plane ticket to Turkey. That same day, his family found an envelope in the mailbox — apparently dropped off by Amin — that contained a thumb drive. The drive had on it family photographs and a note from Niknejad saying that he loved his family but “had traveled to Medina, Saudi Arabia, to further study Islam,” according to the affidavit. Investigators took that to mean he had made it to Syria and would not see his family again.

– – – –

Washington Post staff writers Jennifer Jenkins, Joe Heim and Victoria St. Martin contributed to this report.